Download

Popular Posts

-

Gibboni and the Gibbon: At Stereo Exchange’s annual Spring High-End Audio Show, Roger Gibboni (left) of Rogers High Fidelity debu...

-

Hey, we were in earthquake country, the land from which Carole King may have received inspiration to write, "I Feel the Earth Move...

-

John Atkinson and Stephen Mejias were unable to attend the Munich High End Show this year, so the call went out to the editors of Ste...

-

A reader once noted that I tend to stick with the same reference gear longer than most reviewers. In addition to Audience's Au24e i...

-

Today, Sony announced an end to production on all MiniDisc players. In a few years, MiniDisc production will cease as well. I know w...

-

The name sounds perfect . It fits neatly next to those of Messrs. Leak, Sugden, Walker , Grant, Lumley, and others of Britain's...

-

The Enigmacoustics company from Irvine in California has become renowned for the self-energized, horn-loaded Sopranino electrostatic su...

-

With the introduction of Audio Alchemy's Digital Transmission Interface (DTI) more than three years ago, the company created an ent...

-

If it's rare to go to an audio show and hear most of a company's products set up properly in multiple rooms, it's rarer sti...

-

There's nothing like highlighted text from Stereophile brother Art Dudley to get a fellow writer's attention. Then again, so...

Market information

Blog Archive

-

▼

2013

(510)

-

▼

October

(73)

- Audioquest Dragonfly DAC and Grado SR80i Headphone...

- GoldenEar Technology Aon 2 loudspeaker

- Opera Callas loudspeaker

- TAVES Toronto Starts Friday

- The Entry Level #35

- The Death of an Audiophile

- Recording of November 2013: Another Self Portrait ...

- Whetstone Audio's Rega Hootenanny

- John Zorn@60

- The 10th Annual Rocky Mountain Audio Fest

- VTL/Wilson/dCS—JA's Equal Best Sound at RMAF

- Resonessence Labs Does DSD

- Wavelength and Vaughn

- Bel Canto Looks Good in Black

- Scaena's Silver Ghosts at the Hyatt

- Kronos/Veloce/YG/Kubala-Sosna

- Grace from Volti Audio & BorderPatrol

- SimpliFi dems Klangwerk Speakers

- Paragon–Doshi–Wilson

- Mojo–Atomic Audio Labs–VH Audio

- Audio by Van Alstine amps & Salk speakers

- Low noise, superb sound from Hegel

- HiFi Imports dems Venture, Weiss, Thrax, Enklein

- Aaudio Imports & the enormous Lansche 8.2 speakers

- Gold Sound Premiers Focal Speaker

- Vapor Audio & BMC at the Hyatt

- German Physiks–Vitus–Purist

- Crescendo Hits Some Peaks

- DSD Done Right: Acoustic Sounds' Super HiRez downl...

- CANJAM’s Major Statement

- Brodmann and Electrocompaniet

- Channel D Rocks Rocky Mountain: Goes High, Low, & ...

- JansZen, Bryston, exaSound

- New Gear from Astell&Kern

- Zesto Premiers Power Amplifier

- Xact Audio Showcases Rockport Speakers

- Daedalus–ModWright–WyWires

- Jeff Rowland's Aeris DAC Impresses

- Lawrence's Double Bass

- Dean Peer OKs Trenner & Friedl’s Pharoah

- TAD Goes Blue Smoke

- A New Native DSD Download Site

- Tannoy+VAC+Esoteric+Shunyata=Transcendence

- Zu and Peachtree: A Felicitous Pairing

- Dynaudio + T+A = Power, Speed, & Grace

- AVM & Gauder Akustik

- Legacy & AVM

- Computer Audio—the Big Picture

- Opus 3's Jan-Eric Persson

- Puresound amplification and phono accessories

- Grimm Audio reaches the US

- Nordost’s New Sort Füt

- Sonus faber Scales the Heights

- Parasound, Monitor Audio, Kimber, and more

- Your Final System

- Cary and ADAM Audio

- McIntosh’s New Babies

- DALI's First Active Loudspeaker

- Party in the Music Hall room

- Acoustic Signature Wow

- The 10th RMAF: Pre-Show Libations

- Wharfedale Diamond 10.7 loudspeaker

- Burning Amp's Slow Burn

- The Entry Level #34

- Audio Research Reference CD9 CD player/DAC

- Aesthetix Saturn Romulus DAC/CD player

- David and his Missing Package

- The 10th Rocky Mountain Audio Fest Starts Friday

- AXPONA Acquired by JD Events

- The Roots and Elvis

- Jenny Hval at the Mercury Lounge

- Darcy James Argue and His Steampunk Big Band

- Major Changes for Montreal & New York Shows

-

▼

October

(73)

The Death of an Audiophile

I first met Charles in the 1990s, around the time I began to review recordings and audio equipment. I had just left my apartment and was driving slowly down the street when I spied a somewhat bent-over, wizened-looking man carrying a copy of Stereophile under his arm. My astonishment at discovering another Stereophile reader whom, it turned out, living just two buildings away, brought my car to a sudden halt.

I opened my window. "You read Stereophile?" I exclaimed.

"Why, yes, I do," replied Charles, with that curious mixture of intellectual engagement, hauteur, and combative distance that I was soon to know too well.

So began our friendship. One of the many things that bound us together, in addition to equipment, was our love of classical music. While Charles championed Bruckner, whose music can drive me up a wall, and initially disparaged my beloved Mahler, we both shared a love for renaissance music and "natural" sound.

Within a week, we'd begun sharing recordings and critiquing each other's systems. Mine was certainly in need of improvement. But the system in Charles's apartment occupied another plane entirely.

Charles was an individual for whom the diagnosis Audiophilia nervosa seemed overly generous. In the darkened front room of his extremely stuffy flat, whose windows had not been opened for years, sprawled a system that defied description. To the right of his closely spaced speakers—Charles thought all that "soundstage stuff" was hooey—and not many feet from his ragged couch were his components and cables, positioned in a frightening, widely spaced array that might best be described as a Coney Island roller-coaster run amok.

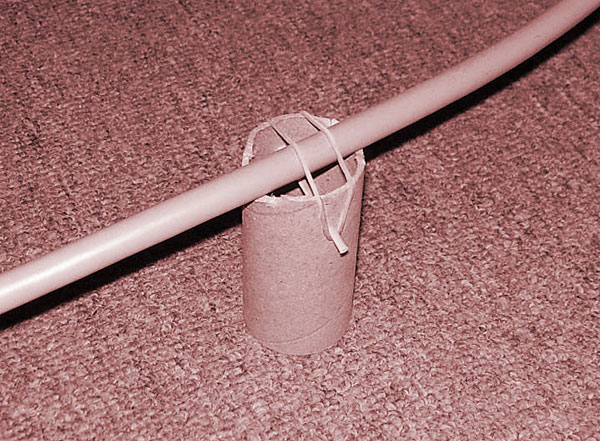

Each component was suspended on a frequently deflating Townshend Seismic Sink and among them ran cable arrays suspended on various homemade contraptions draped with pieces of white silk. Each shred of silk had found its final position through extensive listening to what Charles felt were the ultimate tests of a digital system: a CD of a single lute or theorbo, and a horrible-sounding, early digital, Deutsche Grammophon recording of Herbert von Karajan conducting a Bruckner symphony.

The silk, Charles was convinced, improved the sound. So did the Cable Jackets, more and more of which seemed to appear as the years went on; the Shun Mook devices, some of which were suspended on amazing, 5'-high, Erector Set–like contraptions that increasingly dominated his house of audio horrors; and the ever-proliferating bass traps that, toward the end of Charles's life, completely surrounded his speakers to the point of musical asphyxiation.

Regardless of the efficacy—or lack thereof—of the many tweaks Charles added, he refused to acknowledge that his speakers were an insurmountable problem. (So were mine, but at least I knew it.) He'd bought them used, without having listened to them, after a reviewer for an absolute authority had declared their midrange one of the finest the reviewer had ever heard. It took me but one listen to deduce that the reviewer had dwelt almost exclusively on the speaker's midrange because its tweeter was a bright, edgy travesty.

The speaker was so flawed that the company soon went out of business. But rather than acknowledge that he'd made a mistake and replace them, Charles bought more and more tapestries, Shun Mook devices, and bass traps. He was determined to get that hideous Bruckner CD to sound right.

"Charles," I would say, "that recording is so flawed that if you ever manage to tame its highs and get its midrange to sound full, every other recording in your collection will sound wrong."

Nice try. It was like trying to convince my Jewish mother. Charles bounced from lute to Bruckner and back again. One day, he'd declare that everything sounded right, only to call back the next to complain that he'd been wrong. Then he would shift a single Shun Mook Mpingo disc 1/16", and call me to rejoice—only to later confess that he'd spoken too soon. One longtime audiophile dealer whom Charles paid for advice declared that he'd never met anyone whose ideas of system setup were so diametrically opposed to his own.

Eventually, I decided it would be best to cease listening to and critiquing his system and simply enjoy Charles for who he was. As much as I found it impossible not to laugh at Charles, there was always a warm place for him in my heart. He was, after all, a reflection of my own obsessed self, magnified 50 times in a fun-house mirror. The more I grew to embrace my own inner Charles, the more I loved the original.

Lord knows how many hours a day Charles spent climbing his ladder to suspend more Shun Mook devices and rare tapestries on the wall. Then, one day, when he was in his early 70s, he fell off the ladder and ended up in the hospital. As his diabetes worsened and his heart problems increased, he began to take even more drastic sonic measures. Once, when I shopped for him, I discovered that he'd shrouded his speakers in plastic and draped them with silk and polyester stuffing. The house of audio horrors had become a wax museum.

As his days grew increasingly dominated by visits from doctors, Charles still occasionally called to share his feelings about recordings. During those moments, we felt as one. But when he stopped discussing his system altogether, I feared the end was near.

After David and I bought and moved into our new house, miles away, I saw less of Charles. On Thanksgiving Day, 2011, I was tempted to call, but knowing that he'd undoubtedly chosen to spend the evening alone, I thought it best to wait. When subsequent calls went unanswered, I drove to our old neighborhood. There I learned that, while his neighbors were visiting family for Thanksgiving, leaving no one near to hear his cries, Charles had suffered a diabetic attack, gone into shock, and died alone.

May you rest in peace, Charles. I hope that death has brought you all the glorious Bruckner chorales your heart desired. Know that you were loved.

Source : stereophile[dot]com

Comments[ 0 ]

Post a Comment