Download

Popular Posts

-

Gibboni and the Gibbon: At Stereo Exchange’s annual Spring High-End Audio Show, Roger Gibboni (left) of Rogers High Fidelity debu...

-

Hey, we were in earthquake country, the land from which Carole King may have received inspiration to write, "I Feel the Earth Move...

-

A reader once noted that I tend to stick with the same reference gear longer than most reviewers. In addition to Audience's Au24e i...

-

John Atkinson and Stephen Mejias were unable to attend the Munich High End Show this year, so the call went out to the editors of Ste...

-

Today, Sony announced an end to production on all MiniDisc players. In a few years, MiniDisc production will cease as well. I know w...

-

The name sounds perfect . It fits neatly next to those of Messrs. Leak, Sugden, Walker , Grant, Lumley, and others of Britain's...

-

The Enigmacoustics company from Irvine in California has become renowned for the self-energized, horn-loaded Sopranino electrostatic su...

-

With the introduction of Audio Alchemy's Digital Transmission Interface (DTI) more than three years ago, the company created an ent...

-

If it's rare to go to an audio show and hear most of a company's products set up properly in multiple rooms, it's rarer sti...

-

The floorstanding Canalis loudspeakers in the Spiral Groove room, driven by Qualia digital source and amplification, were new to me, bu...

Market information

Blog Archive

-

▼

2013

(510)

-

▼

March

(71)

- Schiit BiFrost USB and Modi DACs Sweepstakes

- Gibson To Buy Majority Stake in TEAC

- Pass Laboratories XP-30 line preamplifier

- Ypsilon Aelius monoblock power amplifier

- Payday Albums: 3/29/13

- Luxman does DSD

- A Nice, Normal Dude Wins the V-Moda M-80 Headphones

- There's No Business Without Show Business

- Passion of the Hi-Fi: Part II - Dimensions

- News Flash: Oppo now plays DSD files

- When Saints Go Machine: "Love and Respect"

- Sarah Vaughan: "Tenderly"

- Too Many Shows?

- People Watching at the Coup de Foudre Party

- The new TT Two

- Bisson, free

- From the Gutwire

- Sonus Faber's Aïda

- The $5000 System

- Live at Leedh

- Lars at large

- Night Sky Courtesy of Blue Circle Audio

- Great Value from Cambridge Audio

- Gift from a flower to a garden

- DeVore doesn’t bore

- Plug and play

- And they’re off!

- Bel Canto Design C7R D/A receiver

- Velodyne Digital Drive Plus 18 subwoofer

- Snake Ears!

- The Entry Level #27

- Orson Wins a Benchmark!

- Music in the Round #59

- rlabarre Submits His Thoughts on the Audience aR2p...

- Montreal‘s Salon Son & Image Starts Friday

- Payday Albums: 3/15/13

- Blue Smoke's Black Box II

- Multichannel Mytek DSD

- An Effective Dem from Shunyata

- High Water Sound at Axpona

- Icon from the UK

- Audio Note UK

- Money Can Buy You...YG Carmels!

- Modwright: Dynamic And Smooth

- The Real Thing

- Music Hall's Marimba & Ikura

- Audioengine Rocks AXPONA

- The Benchmark DAC2 HGC

- Pure Vinyl & Music from Channel D

- Double DSD from M•A

- Crazy for BAT and Friends

- New Site in Websville

- Quintessence–Sonus Faber–REL–Audio Research

- Fresh Vinyl—Get Your Vinyl Here!

- Ediots . . . I mean Editors and Then Some

- You Never Know Just Who...

- Fosgate and Musical Surroundings' Happy Pairing

- CEntrance: Making Computer Audio Better

- Prepared for Chicago

- Mancave Metal Speakers at Axpona

- Spendor S3/5R2 loudspeaker

- Listening #123

- Video: "3AM" by Kate Nash

- Sexy Shlohmo

- The 2013 Pitchfork Music Fest Announces Initial Li...

- The Shape of Jazz to Come in 45rpm

- Three Days in England with KEF

- AXPONA Chicago Starts Friday

- Anne Bisson at Toronto’s Angie's Corner

- Logitech|UE 900 Noise-Isolating Earphones

- Payday Albums: 2/1/13 & 3/1/13

-

▼

March

(71)

Three Days in England with KEF

“Johan,” I said.

“Hello! You made it!”

He led me from the airport, through the parking garage, and to an impressive black Mercedes. After loading our bags into the trunk, I instinctively walked around to the right-hand side of the car and nearly opened the door.

“Wrong side, mate. Unless you want to drive.”

It was a mistake I’d make a few more times before our three-day trip was over.

I think my first hands-on experience with KEF loudspeakers came back in 2007, when John Atkinson was working on his review of the Reference 207/2 ($20,000/pair), a speaker that’s been rated Class A in our “Recommended Components” list since April 2008. I helped John measure it. By that, I mean I lifted with all my strength as we positioned the curvaceous, 145-lb beauty onto a rotating platform and prayed that it wouldn’t come crashing down. Before that, I took an opportunity to listen to the speakers in JA’s listening room, and I was more than impressed with what I’d heard: It was probably the most dynamic, natural, and compelling sound I’d heard up until that point. John had loved the speakers, too. He concluded his review by saying, “[T]he 207/2 is overall the best-sounding full-range speaker I have used in my current listening room. To all intents and purposes, it is without flaw.”

I filed that away and, from that point on, made sure to listen to KEF speakers whenever I could. Fortunately, opportunities came often: At the 2008 CES, I was mightily impressed by the sound of the smaller Reference 201/2 ($6000/pair). Wes Phillips’ complete review confirmed my thoughts. Wes wrote, “It’s a truism that no transducer is perfect, but the 201/2 Signature is an absolute gem—if not flawless, then damn close.” JA was similarly impressed by the speaker’s performance on the test bench: “The KEF Reference 201/2 is one of the best-measuring speakers I have had the pleasure to test in my lab.”

My attraction to KEF only grew stronger when the company released the striking, limited-edition Muon ($200,000/pair)—a top-to-bottom rethinking of what a speaker could be. Next, at the 2011 Munich High-End Show, I was as much impressed by the sound of KEF’s then-new Blade ($30,000/pair) as I was by the intelligent woman presenting it. KEF’s Julia Davidson was the rare research engineer that could discuss her work in ways that made sense to even the most technologically dimwitted reviewer (me). Plus, she was pretty, smelled nice, and listened to Radiohead.

I was beginning to love KEF.

But, as is so often the case, love turned out to merely be lust. True love came when KEF introduced their 50th Anniversary Edition LS50. A tribute to the famed LS3/5a, the LS50 is a small, two-way, reflex-loaded design that uses KEF’s improved Uni-Q technology to combine a 1” tweeter and a 5.25” woofer in a smart, computer-modeled enclosure. The thing is beautiful. And, at $1500/pair, it’s also affordable. Or, at least, it’s not crazy expensive. Even to me, the worst financial planner on the planet, the LS50 seems obtainable—well worth the time it takes to dream. The LS50 was the talk of the 2012 Munich High End Show, and, later in the year, it was the talk of the Rocky Mountain Audio Fest. Finally, John Atkinson’s review appeared in our December 2012 issue, and while JA didn’t need my help lifting this one onto his rotating platform, the review was nevertheless intriguing. I had to hear these speakers.

When JA’s schedule prevented him from accepting an offer to visit KEF in Maidstone, England, he passed the offer along to me. I was thrilled. The initial plans were made in May, postponed by the London Olympics, postponed again by Superstorm Sandy, and finally set in stone in November. The three-day trip was a whirlwind, but it was also fantastic—an experience I’ll never forget.

In my February 2013 “The Entry Level” column, I wrote a bit about the trip, discussing in particular my experience with KEF’s new powered loudspeaker, the impressive X300A ($800/pair). While in England, in addition to spending quality time with Coorg, I also enjoyed the company of two bright, young KEF team members: KEF UK’s head of marketing, Michael Johnson and another talented research engineer, Jack Oclee-Brown. On the first day of my trip, I received a tour of KEF’s headquarters; on the second day, Johnson, Oclee-Brown, and I drove to the lovely town of Ipswich, where we visited Celestion, KEF’s corporate sibling (both companies are owned by GP Acoustics); and, on the third day of the trip, Johnson and I boarded a train to London, where we did a little casual sightseeing.

***

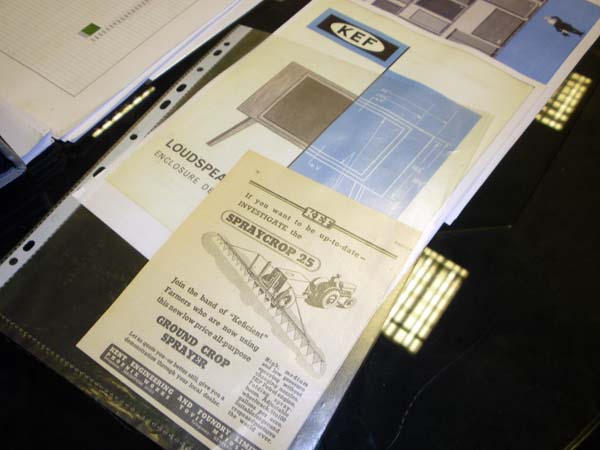

KEF was founded in Maidstone, Kent, in 1961, by Raymond Cooke, and named after Kent Engineering & Foundry, a metal-working operation—“tractors and crop-sprayers”—which formerly occupied the site. UK sales and marketing, the manufacture of flagship products—the Muon, Blade, and Reference loudspeakers—and all research and development, take place here.

The site is a bit of industry tucked into a pocket of green trees—red brick buildings and sliding garage doors beneath a big, blue sky. It reminds me of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. “This Maidstone facility,” Coorg tells me, “is the beating heart of KEF.” He’s clearly proud of the company’s working-class heritage, proud of the fact that KEF has operated in the same location for over 50 years.

“The way we operate today is largely in the same spirit as how we operated at the start. We’ve kept the self-same principles intact. And it goes back to one man: Raymond Cooke. He asked himself, ‘How do we make loudspeakers better?’ That’s our goal—always to improve the art of speaker design, always to improve performance.”

Coorg explains that KEF’s work “has never been about smoke and mirrors. We want to represent real value.” To that end, KEF’s engineers work with “solid science and modern materials.” Coorg tells me that in 1973, KEF became “the first company to use computer-assisted methodology to optimize speaker design.” With their new testing equipment, KEF’s engineers could relatively easily manipulate crossover and drive-unit data, while also improving manufacturing consistency, matching pairs of speakers to within half of a decibel and thereby heightening stereo effects. One of the first KEF speakers to benefit from the new methodology was the Model 104. Continued work with computer-assisted design led to KEF’s development, in 1988, of the Uni-Q drive-unit, “providing, for the first time, a single point source of sound.”

Coorg leads me into the loudspeaker museum at KEF’s Heritage and Innovation Centre. Purposefully placed throughout the room are the KEF 50—well-loved samples of 50 distinct loudspeakers that together create a virtual timeline of the company’s achievements in sound. It’s a marvelous display. Beneath each speaker is a placard detailing its place in KEF’s history. At one end of the room is the legendary BBC LS3/5a, the classic minimonitor that used KEF’s B110 midrange driver and T27 tweeter; demanding attention at another end of the room is the imposing Austin—Coorg’s favorite speaker—the prototype that led to the cost-no-object Muon; the Muon itself remains covered under purple cloth, in an alcove that also holds a complete demo system; and, at the room’s center, is the lovely Concept Blade.

In a tidy but well-worn room, not unlike most small offices in the United States, with workstations separated by partitions and decorated with music posters and decals, I was greeted by a group of kind, intelligent people—just a portion of KEF’s research and development team. Most of them are men, most are surprisingly young, and, while all of them seem very serious about what they do, they are also clearly enjoying themselves. The environment buzzes with the sort of creative energy I commonly equate with an artists’ studio or a university lecture hall. This is where problems are tackled and solved.

Dressed casually in a sweater, khakis, and sneakers, Jack Oclee-Brown is sitting before a computer screen, discussing the day’s work. He says there are always three or four, maybe five or more, different projects taking place at once. Currently, he’s focused on improving some of KEF’s existing drive-units, figuring out a compromise for a new baffle shape, and working on a series of computer models for a future project.

Oclee-Brown is young—he can be no more than 28 years old, I imagine—soft-spoken, and thoughtful. He’s aware that the lines, angles, and values on his computer screen mean little to me, but he manages to nevertheless imbue them with meaning. He reaches for his mouse, drags the cursor across the screen, manipulates the lines, and alters the values. He explains that KEF’s in-house design software, code for which he and his team are constantly developing and improving, enables the precise analysis of speaker behavior in complex environments. Here, on the computer screen, KEF’s engineers can interpret test results in ways that are much more meaningful than would be simple trial and error.

It occurs to me that John Atkinson would love this.

***

Oclee-Brown has been a full-time engineer at KEF since 2004, but began working with the company as an intern in 2002. While in university, Oclee-Brown wrote to every loudspeaker company in the UK, looking for work. “KEF,” he laughs, “was the only company that replied.” It seems to have worked out well for both parties: Oclee-Brown has just earned a Ph.D. in the acoustics of compression drivers and holds a particular fondness for KEF’s Uni-Q driver array, an elegant and intelligent concept that he believes is finally reaching its performance potential.

Our conversation moves easily, seamlessly, between sound and music and from the recording studio to the listening room. And when we turn to the well-worn topic of accuracy vs musicality, Oclee-Brown surprises me: “I don’t necessarily believe that poorly recorded music played through a good loudspeaker should sound bad.”

This, to me at least, is a refreshing and attractive perspective, and one I wouldn’t expect to hear from a loudspeaker engineer. The typical viewpoint is that a high-fidelity loudspeaker will faithfully reproduce the signal: garbage in, garbage out. “But almost every piece of music has been mastered,” Oclee-Brown says. “It sounded good to someone at some point.” While a properly balanced loudspeaker will draw the best from a recording, the typical “fatiguing” loudspeaker is the product of poor engineering—an effort to create the impression of more detail or clarity through aggressive tuning of the high frequencies. “If you’re scraping for detail and clarity at the balancing stage, you’ve done something wrong. You shouldn’t have to put an emphasis on treble clarity to get good detail.”

Oclee-Brown is interested in optimizing KEF’s Uni-Q design to produce a wide, consistent dispersion, putting more treble into the listening room without actually boosting the treble level.

He speaks passionately about the potential of modeling within a system. “Everything now is designed to work together,” he explains, pointing to the screen. “Here we see a tweeter, dome, and wave-guide, all working together.” He talks about “modeling reality,”—in this case, the ability to use computer software, accurately and intelligently, to manipulate data in ways that will directly relate to performance in the listening room.

Turning our attention to a speaker cabinet, Oclee-Brown describes a situation in which not only the obvious cabinet materials, but also the internal bracing and air are evaluated to ensure a good match between the model and the real world. “In this way, we can very easily make changes and improvements.”

Finally, it was time to do some listening. Three seats were set up facing a demo system comprising Arcam’s top-of-the-line C37 CD player and D33 DAC, a MacBook, and Chord Company cables. Arcam’s A38 integrated amplifier was matched with the LS50s, while Electrocompaniet’s Nemo monoblocks drove the Blades. Listening first to the LS50s, I noted an uncommonly smooth overall sound, with warmth matched by detail, and an almost incredible sense of space and bloom: the music grew in size and intensity, naturally and seemingly effortlessly. A piano piece showed off the system’s sense of touch, delicacy, and truth of timbre. I noted outstanding leading-edge articulation, graceful decays, and, again, “so much beautiful space.”

Switching to the Blades, I heard no loss of clarity, impact, or imaging abilities, but noted improved richness to the voices; greater weight, force, and overall extension; and a larger soundstage. Listening to a high-rez file of a Joni Mitchell track, it was easy to imagine myself in a smoky jazz club: horns had the right combination of sweetness and bite, cymbals just the right amount of sizzle and splash. And when John Coorg cued up Prince’s N.E.W.S., I was almost immediately transported by the music. “Completely captivating.”

On the second day of my trip to England, we visited the headquarters of KEF’s corporate sibling, Celestion, where we learned a bit about how Celestion drivers are developed and manufactured. While the companies largely exist independently, KEF and Celestion do share some research and development resources—at the time of my visit, Jack Oclee-Brown was working with Celestion to develop very large tweeters. “The success of a driver greatly depends on everything being small,” said Oclee-Brown. “As you make it bigger, the acoustics become more challenging. I’m working to make it as simple as possible.”

Still, the two companies take radically different approaches to design. While a typical hi-fi speaker company will strives to eliminate harmful vibrations, Celestion’s engineers encourage vibrations—“but only the ones in the right places,” explained Celestion’s marketing manager, John Paice.

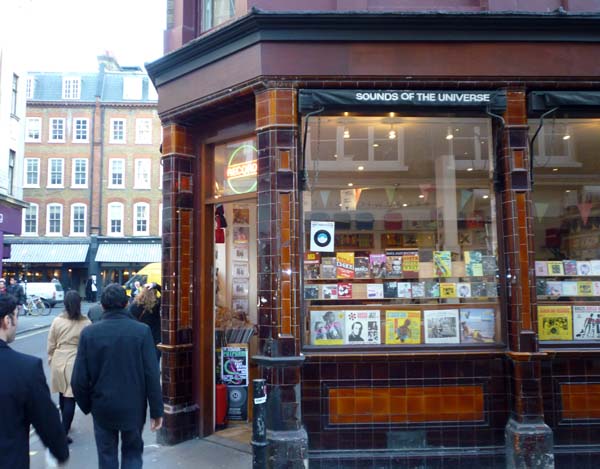

Of course, we stopped in every record shop we saw. From top: The legendary Sister Ray, Reckless Records, Music & Video Exchange, and my very favorite, Sounds of the Universe. Amazingly, these were all just blocks (and sometimes mere steps) away from one another. I was in heaven.

Or at least I thought I was in heaven.

Heaven truly came when Michael Johnson and I stopped for lunch at Mother Mash, where lucky customers are invited to create the perfect meat pie using a three-step process: Choose your mash, choose your main, choose your gravy. I came up with a cheesy, mustard mash with chicken, leek, and ham pie, topped with the Farmer’s Gravy (red wine, caramelized onion, smoked bacon, and mushrooms).

God, I can almost taste it now. Every night before I go to bed, I pray that someone will open a Mother Mash in Manhattan.

Michael Johnson and I ended our day in London the right way—with pizza, wine, and outstanding live music by the Will Vinson Quartet in the intimate Pizza Express nightclub. Vinson and his group—Lage Lund (electric guitar), Matt Brewer (bass), and Rodney Green (drums)—put on a remarkable performance: Vinson was agile and fluid on sax, delivering catchy melodies with a smooth, clear tone; Brewer and Green exhibited a deep trust and bond, moving easily, swinging, swaying, staggering, and soaring; while Lund provided interesting, angular counterpoint to Vinson’s sweet lines. This was the perfect way to end an excellent three days in England.

Becoming better acquainted with KEF’s people and products has only reinforced my feelings about the company’s integrity, engineering skill, and dedication to quality and innovation. Now more than ever I feel determined to own a pair of KEF loudspeakers. And while I can very easily see the LS50 in my future, I also look forward to seeing and hearing what KEF comes up with next.

Cheers!

Source : stereophile[dot]com

Comments[ 0 ]

Post a Comment