Download

Popular Posts

-

Gibboni and the Gibbon: At Stereo Exchange’s annual Spring High-End Audio Show, Roger Gibboni (left) of Rogers High Fidelity debu...

-

Hey, we were in earthquake country, the land from which Carole King may have received inspiration to write, "I Feel the Earth Move...

-

A reader once noted that I tend to stick with the same reference gear longer than most reviewers. In addition to Audience's Au24e i...

-

John Atkinson and Stephen Mejias were unable to attend the Munich High End Show this year, so the call went out to the editors of Ste...

-

Today, Sony announced an end to production on all MiniDisc players. In a few years, MiniDisc production will cease as well. I know w...

-

The name sounds perfect . It fits neatly next to those of Messrs. Leak, Sugden, Walker , Grant, Lumley, and others of Britain's...

-

The Enigmacoustics company from Irvine in California has become renowned for the self-energized, horn-loaded Sopranino electrostatic su...

-

With the introduction of Audio Alchemy's Digital Transmission Interface (DTI) more than three years ago, the company created an ent...

-

If it's rare to go to an audio show and hear most of a company's products set up properly in multiple rooms, it's rarer sti...

-

The floorstanding Canalis loudspeakers in the Spiral Groove room, driven by Qualia digital source and amplification, were new to me, bu...

Market information

Blog Archive

-

▼

2013

(510)

-

▼

March

(71)

- Schiit BiFrost USB and Modi DACs Sweepstakes

- Gibson To Buy Majority Stake in TEAC

- Pass Laboratories XP-30 line preamplifier

- Ypsilon Aelius monoblock power amplifier

- Payday Albums: 3/29/13

- Luxman does DSD

- A Nice, Normal Dude Wins the V-Moda M-80 Headphones

- There's No Business Without Show Business

- Passion of the Hi-Fi: Part II - Dimensions

- News Flash: Oppo now plays DSD files

- When Saints Go Machine: "Love and Respect"

- Sarah Vaughan: "Tenderly"

- Too Many Shows?

- People Watching at the Coup de Foudre Party

- The new TT Two

- Bisson, free

- From the Gutwire

- Sonus Faber's Aïda

- The $5000 System

- Live at Leedh

- Lars at large

- Night Sky Courtesy of Blue Circle Audio

- Great Value from Cambridge Audio

- Gift from a flower to a garden

- DeVore doesn’t bore

- Plug and play

- And they’re off!

- Bel Canto Design C7R D/A receiver

- Velodyne Digital Drive Plus 18 subwoofer

- Snake Ears!

- The Entry Level #27

- Orson Wins a Benchmark!

- Music in the Round #59

- rlabarre Submits His Thoughts on the Audience aR2p...

- Montreal‘s Salon Son & Image Starts Friday

- Payday Albums: 3/15/13

- Blue Smoke's Black Box II

- Multichannel Mytek DSD

- An Effective Dem from Shunyata

- High Water Sound at Axpona

- Icon from the UK

- Audio Note UK

- Money Can Buy You...YG Carmels!

- Modwright: Dynamic And Smooth

- The Real Thing

- Music Hall's Marimba & Ikura

- Audioengine Rocks AXPONA

- The Benchmark DAC2 HGC

- Pure Vinyl & Music from Channel D

- Double DSD from M•A

- Crazy for BAT and Friends

- New Site in Websville

- Quintessence–Sonus Faber–REL–Audio Research

- Fresh Vinyl—Get Your Vinyl Here!

- Ediots . . . I mean Editors and Then Some

- You Never Know Just Who...

- Fosgate and Musical Surroundings' Happy Pairing

- CEntrance: Making Computer Audio Better

- Prepared for Chicago

- Mancave Metal Speakers at Axpona

- Spendor S3/5R2 loudspeaker

- Listening #123

- Video: "3AM" by Kate Nash

- Sexy Shlohmo

- The 2013 Pitchfork Music Fest Announces Initial Li...

- The Shape of Jazz to Come in 45rpm

- Three Days in England with KEF

- AXPONA Chicago Starts Friday

- Anne Bisson at Toronto’s Angie's Corner

- Logitech|UE 900 Noise-Isolating Earphones

- Payday Albums: 2/1/13 & 3/1/13

-

▼

March

(71)

Listening #123

Of far greater importance, of course, is the artistry between its covers: The person who, in 2013, buys an ink-and-paper copy of In Cold Blood is guaranteed the same reading experience as the person who bought his or her copy on the day the book was first released. That's how the publishing industry works, God bless them.

The idea behind the recording industry purports to be the same, but the reality is different: The consumer who, in 1966, bought a copy of Leonard Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic performing Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde was rewarded with one experience. The person who bought the same thing 40 years later got something else altogether.

And it's a shame, because that Mahler recording is important: As important in its own way as In Cold Blood, or any number of other buyable works of art.

I feel the same way about the Beatles catalog. Their music is as important as it is charming and fun and adventurous. I can't imagine a time when the Beatles' reputations as writers, arrangers, and performers—as artists and innovators—won't be held in the same high esteem as they are today.

But the person who, in 2013, takes an interest in hearing the Beatles for the first time will not hear them at their best, because all the currently available commercial recordings of their work are presented in digital sound rather than the recordings' native analog. And although much of that digital sound is good digital sound, it isn't up to the best analog standards. At the same time, the digital sound of some selections in the Beatles catalog is downright mediocre—and not because contemporary digital technology is so good that it exposes "flaws" in the original: a lie of which the technopologists in the recording and audio industries never seem to tire.

Not only that, but those digital files, good and not-so-good alike, represent not the original analog master tapes, but versions of same that were subjected to modern reequalization and compression, the primary purpose of which was apparently to boost the bass content in an effort to create a sound more appealing to modern listeners (footnote 1).

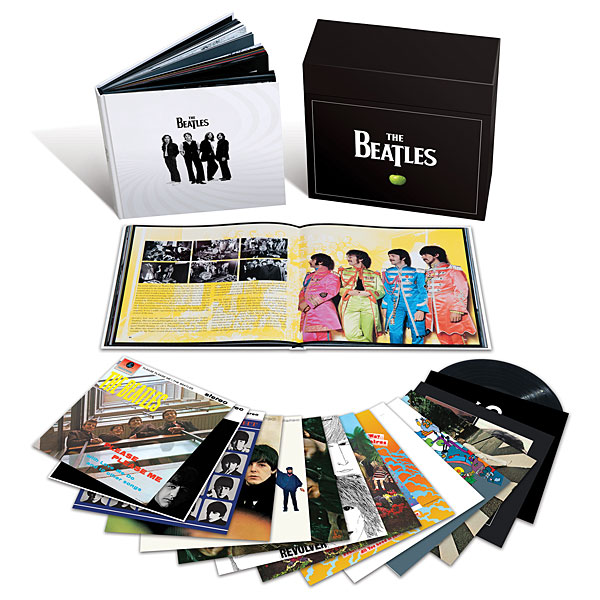

Not only that, but the recent and richly ballyhooed reissues of the Beatles albums on LP—sold singly or as The Beatles Stereo Vinyl Box Set (Apple AEMI 33809)—were all mastered not from the original analog master tapes but from 24-bit/44.1kHz digital copies (footnote 2) thereof (a revelation that comes courtesy of my friend and colleague Michael Fremer, who broke the story on AnalogPlanet.com).

The people responsible for this new wave of LP reissues imply that it was their concern for the fragile and irreplaceable analog master tapes that led them to cut the new vinyl from digital files. I would suggest that the cutting of new analog masters is precisely the sort of project for which such tapes are kept and preserved in the first place: If not for this, then what? Another, presumably more "perfect" wave of digital remakes every 15 years?

The people responsible for the new LP reissues imply that 44.1kHz digital is good enough for what we are led to believe will be the last series of Beatles LPs. I, on the other hand, would suggest that good enough is not good enough. I think the consumer of 2013 ought to be able to enjoy any music—let alone the Beatles, for God's sake—in sound that is at least as dynamic, natural, colorful, wide of bandwidth, and altogether listenable as when the recordings first came out. Hearing these recordings at their best should not be the privilege of only a relative handful of fortunate record collectors. Yet with every new wave of reissues—or, in the case of the dubious Love LP and DVD-A, reimaginings—we are given considerably less than the best, all while being asked to pay for the same music over and over again. Perhaps the time has come to rock the boat.

Doris gets her oats

Let's pause to consider an important point: A signal that has been digitized is a signal that has been digitized, period. Once you convert an analog music recording—a thing of virtually infinite resolution and remarkable complexity—into a digital file, you have reduced the amount and the density of data in that recording by at least some degree. After A/D conversion, you can do any number of things with that file, the most common being to convert it into a new analog signal, but the latter will no longer be exactly the same as the original.

In a domestic playback system, D/A conversion is usually performed just upstream of the preamplifier. However, if you prefer, you can have your digital recordings converted even further upstream: by the company from which you buy them, at the LP-mastering stage, right before they're pressed onto vinyl. Considered as mere data, there's no difference between the two, and to expect better, more analog-like sound from the latter than from the former would seem an expression of the most ardent optimism. Or, as I stated in the June 2012 edition of this column: "[A]n analog pressing of a digital recording is still a digital recording. And the 'better' the mastering job, the more digital the results will be. If you leave a pointillist watercolor out in the rain, dots will run. But they're still just dots."

But I admit, I've noted one respect in which digital recordings do seem to sound better when played back via the analog medium of phonography: They seem capable of sounding more physical than they do via CD or streaming file, with a distinctly better sense of touch of mallet on drum, plectrum on string, that sort of thing. Whether this is something that digital playback technology simply can't do very well in its present state, or whether there's some arcane relationship between physical media (as opposed to the mere moving of electrons) and the physicality of sound, I don't know (footnote 3). I'm at peace with the possibility that I'm deluding myself, and with the even more seditious possibility that, if I'm not delusional, the thing that I'm hearing and enjoying is a distortion. Big deal.

And so it was that I approached with an open mind the opportunity that I found in November: My friend Sasha Matson had just received his own Stereo Vinyl Box Set, pre-ordered earlier in the year, but his immediate travel plans prevented him from listening to it for another couple of weeks; Sasha wondered if I would like to borrow the box for a few days—thus giving me a chance to audition all 16 discs and to compare them with my own collection of Beatles recordings.

I began in the middle, comparing the new version of Revolver with my own original Parlophone stereo copy of same, the latter being in mint-minus shape. The first thing I noticed about the new release was nothing: absolutely no surface noise whatsoever. I didn't hear one single tick or pop, nor the slightest hint of groove-grunge, at any time while auditioning this record. The same was true of every LP in the box—all of which, I should add, were also supremely flat: a "Stop there" recommendation for some record lovers, and I don't suppose I blame them.

That said, I was surprised that Revolver—which I consider one of the Beatles' best-sounding recordings—was among the albums most poorly served by Apple's recent remastering job. On the original, for example, Paul McCartney's voice in "For No One" is colorful and immediate: almost startlingly well recorded. On the new LP, however, he sounded veiled and chalky by comparison: characteristics that marred the vocals on almost every track on this disappointing reissue.

I decided then to take a less scattershot approach, and went back to the beginning of the collection—and was rewarded, to at least some extent, for my effort. The reissue of the first title, Please Please Me, sounded quite good: open, clear, and crisp whenever called for, but without being brittle. And the physicality of the playing was indeed superb: Check out the very deliberate arpeggio with which George opens "Misery," and his chording and single-note work in "Ask Me Why." Ringo's drumming sounded similarly fine—if compressed, overall, in the original recording—as did the percussive note attacks in Paul's conspicuously boosted electric-bass lines.

With the Beatles brought more of the same good clarity and physicality. And in numbers such as "All I've Got to Do," the LP was more realistic and listenable than the 2009 stereo CD reissue, the CDs making a mushy, crunchy mess of such things as vigorously struck hi-hat cymbals.

Then I ventured into The Unknown: My own collection of Beatles albums, such as it is, comprises two original Parlophone monos, one original Parlophone stereo, a German EMI/Odeon, and a mix of American and Canadian Capitols—but I've never owned a vinyl copy of A Hard Day's Night, and thus have no way of knowing if the original recording has the same brittle top-end crunch I hear on the new LP—and, for that matter, the 2009 and 1988 stereo CDs. Of all the A Hard Day's Night releases I've heard, the mono CD of 2009—available only as part of the boxed set The Beatles in Mono—is by far the most tolerable and impactful. I can only assume that an original mono LP is better still, while admitting that the 2012 LP, though not a terribly good-sounding thing in and of itself, might well be among the more acceptable alternatives.

Footnote 1: I can assure you, the irony of a "Listening" column sniffing at those who would sacrifice authenticity in favor of pleasure is not lost on me.

Footnote 2: These are apparently the same 24/44.1k remasterings, downsampled from 192kHz originals, that were released in that resolution as FLAC files on a USB dongle in 2009. The 2009 CDs were decimated to 16-bit word length, of course. See Robert Baird's article on the remastering in the October 2009 issue of Stereophile.—Ed.

Footnote 3: And, yes, it's another of those things that the combination of a low-compliance pickup and a high-torque turntable motor do far better than their wimpier cousins.

| | |||||||||

Source : stereophile[dot]com

Comments[ 0 ]

Post a Comment