Download

Popular Posts

-

Gibboni and the Gibbon: At Stereo Exchange’s annual Spring High-End Audio Show, Roger Gibboni (left) of Rogers High Fidelity debu...

-

Hey, we were in earthquake country, the land from which Carole King may have received inspiration to write, "I Feel the Earth Move...

-

A reader once noted that I tend to stick with the same reference gear longer than most reviewers. In addition to Audience's Au24e i...

-

The Enigmacoustics company from Irvine in California has become renowned for the self-energized, horn-loaded Sopranino electrostatic su...

-

Today, Sony announced an end to production on all MiniDisc players. In a few years, MiniDisc production will cease as well. I know w...

-

The name sounds perfect . It fits neatly next to those of Messrs. Leak, Sugden, Walker , Grant, Lumley, and others of Britain's...

-

Silicon Valley–based Velodyne was founded in 1983 to develop a range of subwoofers that used servo-control to reduce non-linear distorti...

-

I've heard a lot of great audio components over the years, but even in that steady stream of excellence, a few have stood out as so...

-

I've long kept an eye on Michael Creek's loudspeakers (Epos) and electronics (Creek). He's always moving forward, with eith...

-

You don't need me to tell you that listening habits are changing. Although those who predict that the end of our beloved home stere...

Market information

Blog Archive

-

▼

2014

(109)

-

▼

January

(87)

- AURALiC VEGA D/A processor

- Matt Wilson's Gathering Call

- Epos Elan 10 loudspeaker

- The Entry Level #38

- As We Listen, So We Are

- Recording of the Month: Classified: Remixed and Ex...

- Digital Demo at Coup de Foudre

- Mary Halvorson’s Illusionary Sea

- What to Make of CES 2014 and Beyond?

- JA’s Best Sound at CES: Vandersteen’s Model 7 Spea...

- Naim’s Statement Amplifier

- Wilson’s New Sasha

- Vivid’s new Giya G4

- Pass Labs Pays Tribute to Sony

- Magico's New S3

- The Ultimate Magico

- DartZeel's Integrated Streaming Amplifier

- Meridian’s Bob Stuart & 25 Years of Digital Loudsp...

- YG’s Hailey

- Marten’s Coltrane Supreme 2

- GoldenEars’ New Triton 1

- Enigma Introduces Complete Speaker

- Warmth from Zesto

- MAD as Hell?

- Handsome Klangwerk from Switzerland

- Cary Audio DMS-500 Digital Music Streamer

- Prismatic Sound from Joseph Audio

- Vienna Acoustics’ Imperial Series Liszt

- Eclipse Back in the USA

- The Canalis Amerigo speaker

- MartinLogan’s Motion Series Speakers

- Krell's new iBias Amps

- PrimaLuna's forthcoming Dialogue Premium HP

- Creek EVO 50CD Player/DAC

- Resolution Audio

- Arcam’s FMJ A49 Mega integrated amplifier

- ADAM’s Tensor Beta Mk.II

- The Tannoy Kingdom Royal Carbon Black Edition

- The Usher Grand Tower

- Rosso Fiorentino, Graaf, and More

- Graaf, Rosso Fiorentino, and More

- Dan D'Agostino Master Audio Systems' Eye Candy

- Dynaudio Updates Excite Series

- Dynaudio Drops XEO Prices

- Genesis Muse Music Source (G-Source)

- Bel Canto Black ASC1 Preamp/DAC

- Project DAC BOX RS

- The Heart of Manley Labs

- Audio Arts & Zellaton's Reference loudspeakers

- ATC & Antelope

- Angelic Sound

- One touch—the BeoSound Essence

- Astell&Kern Branches Out

- Bam Bam from Tyr-Art

- VAC's Soon-to-Emerge Preamp

- Nagra HD DAC

- MBL Revamps its Noble Line

- Cozying up with Rogue's Egyptian Royalty

- BAT's Big Change

- Constellation Comes Nearer to You

- The New 6T from Aerial Acoustics

- BSG's øReveel

- New from Epos at the 2014 CES

- Light Harmonic, LH Labs, & Indiegogo

- On The Left: PCM

- On The Right: DSD

- Weiss DAC202 DSD Update

- Macintosh MB100 Media Bridge

- The Nicolls

- Peachtree's Sweet Nova

- Flying by Moon with Simaudio

- LA Audio . . . from Taiwan

- Stereophile's Products of 2103

- New DSD DACs from Korg

- PSB's Desk-Top Subwoofer

- Chord Hugo DAC/Headphone Amp

- Inside Llewyn Davis

- Esoteric Grandioso D1 Monoblock DAC

- Aesthetix Romulus and Pandora Signature Upgrades

- Accuphase DP-720 SACD/CD Player

- Olasonic Nano Campo Line

- Arcam miniBlink Bluetooth Streaming DAC

- Antelope Rubicon Atomic AD/DA Preamp Appears

- Light Harmonic Sire DAC

- dCS Vivaldi digital playback system

- Old and New: A 2014 Resolution

- The Ultimate Headphone Guide: Now Available for Pu...

-

▼

January

(87)

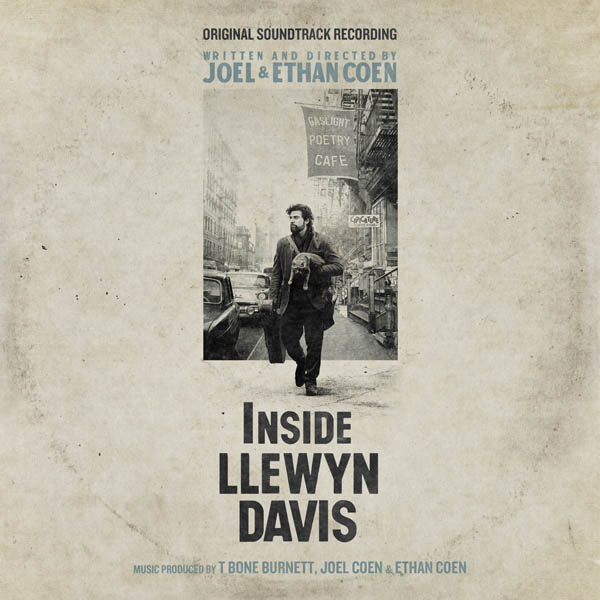

Inside Llewyn Davis

Given all that, Inside Llewyn Davis, may also be the most powerful Coen Brothers film yet. Easy to dislike, the title character played by Oscar Isaac is a frustrated 60’s folksinger/searcher who is volatile, irresponsible and ultimately a failure; yet he effectively draws you into another of the Coen’s otherworldly environments where what’s happening inside of characters often informs the physical world around them. In this case, that means endless chaos and struggle, made harder by poor decisions and selfish mistakes. Only in a Coen Brothers film could scenes with cats become the most poignant and sad moments in an otherwise downcast film. As it was with Fargo’s slightly surreal Twin Cities, the Washington Square milieu of Inside Llewyn Davis feels like an LP played at an uncertain speed; still real but just a tick off being firmly in this dimension. Filmed in a stark palette of grays and dark greens, this is not the big exuberant live action cartoon that O’ Brother, Where Art Thou was. And the soundtrack, another product of the Americana–leaning ears and refined sensibilities of T–Bone Burnett, mixes bruised if not bleeding chunks of Mahler, Chopin and Mozart (whose Requiem is today’s all–purpose source of gravitas for film music directors) with traditional tunes like “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” and folk standards like Ewan MacColl’s “Shoals of Herring.” Doleful is the dominating vibe—there’s nothing as catchy or upbeat as “Man of Constant Sorrow,” here. Cross–promoting soundtrack album and film to benefit the other will be a stretch this time out. Lightning, in this case, will not strike twice.

In all fairness, as a Gotham dweller who writes about music, this film’s dark powers roused me more than most. In some ways—and I won’t spoil a near–the–end surprise—it is a snapshot of the Greenwich Village folk scene of the early Sixties. The Bud Grossman character played by F. Murray Abraham is clearly based on Dylan manager Albert Grossman. The record producer, Mr. Cromartie, played by Ian Jarvis, who sways in the control room during a recording session, has the unmistakable chiseled visage of John Hammond. And then there’s the scene where Oscar Isaac’s Davis visits the mute, ailing father who’s being warehoused in a sad, concrete block institution, and who despite difficulties is still his mentor—all of it an obvious echo of Dylan visiting Woody Guthrie at one of the New York area mental hospitals he was confined in from 1956 onwards.

A character who elicits little sympathy early in the film, Isaac’s performance gathers a puzzling, directionless energy that keeps you watching a tale that in some ways, you come to suspect, follows Davis’ dictum about folk music which is, “never new and never gets old.”

Source : stereophile[dot]com

- Không có bài viết liên quan

Comments[ 0 ]

Post a Comment