Download

Popular Posts

-

Gibboni and the Gibbon: At Stereo Exchange’s annual Spring High-End Audio Show, Roger Gibboni (left) of Rogers High Fidelity debu...

-

Hey, we were in earthquake country, the land from which Carole King may have received inspiration to write, "I Feel the Earth Move...

-

A reader once noted that I tend to stick with the same reference gear longer than most reviewers. In addition to Audience's Au24e i...

-

The Enigmacoustics company from Irvine in California has become renowned for the self-energized, horn-loaded Sopranino electrostatic su...

-

Today, Sony announced an end to production on all MiniDisc players. In a few years, MiniDisc production will cease as well. I know w...

-

The name sounds perfect . It fits neatly next to those of Messrs. Leak, Sugden, Walker , Grant, Lumley, and others of Britain's...

-

Silicon Valley–based Velodyne was founded in 1983 to develop a range of subwoofers that used servo-control to reduce non-linear distorti...

-

I've heard a lot of great audio components over the years, but even in that steady stream of excellence, a few have stood out as so...

-

I've long kept an eye on Michael Creek's loudspeakers (Epos) and electronics (Creek). He's always moving forward, with eith...

-

You don't need me to tell you that listening habits are changing. Although those who predict that the end of our beloved home stere...

Market information

Blog Archive

-

▼

2013

(510)

-

▼

July

(24)

- Bill Frisell’s Big Sur

- Wilson Audiophile Recordings Return

- Capital Audiofest, Wrap-Up

- Capital Audiofest, Day One

- Pre-road downs

- Astell&Kern AK100 portable media player

- I'd Love to Turn You On

- Home Theater Merges with Sound & Vision

- 2013 Recommended Components

- The Good Rats' Peppi Marchello dies at 68

- Emily Tries but Misunderstands

- Amar G. Bose, PhD: 1929–2013

- Wayne Coyne

- Wadia 121decoding Computer D/A processor

- Recording of February 1984: Beethoven/Enescu Violi...

- CAD Audio MH510 Headphone Sweepstakes

- The Big Dream & “The Vastness of the Small Corral”

- Music in the Round #61

- Video: Julia Holter's "In the Green Wild"

- (Mostly) Analog Adventures By the Bay

- Yves-Bernard André: Kind of Blue

- CE Week: Headphones Galore, A DAC, A Small Hi-Fi, ...

- Pioneer SP-BS22-LR loudspeaker

- Listening #127

-

▼

July

(24)

Wilson Audiophile Recordings Return

As I learned in a phone chat with Wilson, by the time he released the game-changing WAMM loudspeaker in November 1981 and left Cutter Labs, where he designed medical equipment in April 1982, he had already spent five years recording musicians and music that he loved. In fact, the main impetus for designing the WAMM was his discovery that the reference loudspeakers he initially tried to use could not adequately convey all the information on his recordings.

"I was hearing the real music, and then trying to make the loudspeaker sound like it," he says. "Today, when I hear orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic, I listen specifically for sound qualities that I find rewarding, and trying to capture those in the sound of the loudspeakers. If, for example, I hear tenor Rolando Villazón when he's rehearsing and go 'Wow,' I try to figure out what qualities in his sound elicit my reaction, and then work to get my loudspeakers to evoke the elements of his sound that generate the same emotional response. Sometimes, I discover the limitations are in the recordings themselves; other times, I realize that I can do better."

Between 1977 and 1995, Wilson made 33 recordings, 27 of which were released to the public. (The rest were privately commissioned by artists, and never intended for public release.) Using minimal miking and custom-modified recording equipment, Wilson continually refined his recording skills and technique as he sought to get "up close and personal" with the sound of musicians and music he loved. As he explains in an online video, his recordings reflect how he preferred to hear music in live performance.

In preparing the recordings for digital release, Wilson worked closely with Bruce Brown of Puget Sound. Offered a choice between a number of analog-to-digital converters, Wilson discovered big differences in their sound. His eventually settled on a Meitner unit, which, he contends, creates transfers that "sound much better than the CDs, and, in some cases, as good or better than the LP."

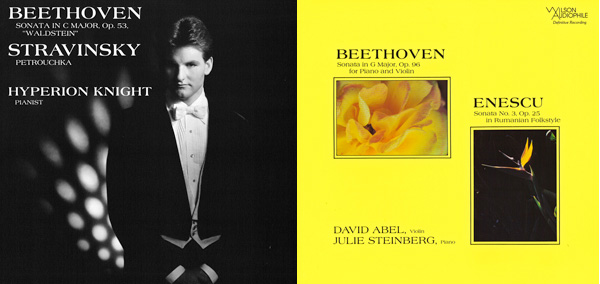

Many of Wilson's recordings of chamber, organ, big band, and jazz met with critical and public acclaim, with a number of LPs earning a place on Harry Pearson's oft-changing Best-Sounding lists. HP loved pianist Hyperion Knight's Beethoven "Waldstein" Sonata and Stravinsky Petrouchka, and the Symphonic Winds' recordings Center Stage and Winds of War and Peace. Stereophile, in turn, heaped praise on Steinberg and Abel's renditions of Beethoven's Sonata in G major, Op.96 and Enescu's spicy Sonata No.3, Op.25 (in Rumanian Folkstyle).

Recital

Wilson recalls attending an organ concert in San Francisco's Grace Cathedral and hearing young Stanford University doctoral candidate, James B. Welch. "I've got to record this guy," he thought to himself. A look at the catalog number for the LP of Recital, W-782, reveals that it was Wilson's second recording, made in 1978.

For the recording, he chose the Flentrop tracker organ in All Saints Episcopal Church in Palo Alto. "I absolutely adore these organs for their articulation, detail, and harmonic structure," he says. "It's delightful to me."

For the session, he used AKG 414 microphones in the hyper-cardiod pattern pioneered by the BBC, a 15ips, half-track Revox A77 with modified electronics and cabling, and an Audio Research SP-3 preamp whose phono input was modified to a microphone input. With the AR's power supply separated and isolated from the chassis, Wilson says it sounded "dramatically better" than the stock unit.

Beethoven and Enescu Sonatas

While Wilson had already recorded piano by the time he began working with world-class musicians Steinberg and Abel in the Mills College Concert Hall in Oakland, CA, it was the first time he recorded a violin. Experimenting with different microphone positions in an attempt to capture what he calls the "delicious geometry" of sound emanating from Abel's Guarneri and Steinberg's Hamburg Steinway D, he ended up hanging his Schoeps CMC-36 microphones from a ladder high above the instruments. Of the results, he says, "I'd put the recording up against any chamber music recording. It has to be my favorite."

Reached at their home in Oakland, Steinberg and Abel, whose trio with percussionist William Winant has commissioned music from the likes of John Harbison, Lou Harrison, Paul Dresher, Somei Satoh, and Gordon Mumma (for starters), reminisced about their time with Wilson.

"The session was free of the time pressure and tension that can really get in the way of the final outcome," says Abel. "If we wanted to stop for a bite, or go outside to rest for a while, that was not a problem... Dave kept open to what was happening in the moment, as in a concert. He understood about not making a 'perfect' recording, and instead left the small imperfections... that make the final result sound human and real. One could not ask for better.

"Dave has one of the most sophisticated and perceptive set of ears that I have ever encountered in the recording world. It was amazing the things he would notice. He had an acute sense of the difference between the two instruments, as well as of their melding and blending. It was the awareness one would expect from a musician."

Steinberg recalls that the takes were extremely long, sometimes for an entire movement, with just a few little fix-ups required.

"I didn't feel like I was working for Dave—we were all in this thing together, working to create the recording," she reports. "Dave was the easiest person in the world to work with. He never lost his cool, and was very calm, steady, and patient. He had tremendous energy, and was very accommodating. It was so unlike other recording sessions that I've been in that are tense and structured, with orders barked at us. It was the closest experience I've ever had to creating [an actual] performance. That's why the editing was minimal."

She contrasts Wilson's goal, which was to recreate the experience of live performance, with that of producers and engineers who insist on editing out the naturally occurring imperfections that invariably flavor live performance.

"I think that's impacting what audiences expect in a concert hall," she opines. "They expect to hear what's on the record. It generates a kind of practice on the part of musicians that is absolutely predictable and sounds like the recording."

As for Wilson's take on what he was doing, he says, with extreme honesty, "I was making those recordings for me, frankly. I just wanted that live sound. But capturing it is a real challenge."

As to how well he succeeded, and how good his taste in music and musicians is, you can now hear for yourself. Judging from the few, short, deliciously color-saturated and detailed 176.4/24 clips I have auditioned through Wilson Audio Specialties W/P Sasha loudspeakers; Pass Labs XA 200.5 class-A monoblock amplifiers; dCS's Puccini CD/SACD player/Scarlatti U-Clock combo; Nordost's Odin cabling, brass and titanium Sort Kones, and full compliment of power distribution/noise control devices; Magico QPods; and Synergistic Research's Active USB cable and Tranquility Bases enhanced by their Transporter UltraSE, PowerCell 4 SE, and ART system, I think Wilson is likely to receive your two thumbs up.

Source : stereophile[dot]com

- Không có bài viết liên quan

Comments[ 0 ]

Post a Comment