Home » Archives for December 2012

Download

Popular Posts

-

A reader once noted that I tend to stick with the same reference gear longer than most reviewers. In addition to Audience's Au24e i...

-

Gibboni and the Gibbon: At Stereo Exchange’s annual Spring High-End Audio Show, Roger Gibboni (left) of Rogers High Fidelity debu...

-

John Atkinson and Stephen Mejias were unable to attend the Munich High End Show this year, so the call went out to the editors of Ste...

-

One of the most striking aspects of high-end audio is that you can never take any component for granted. Most of the radical change in ...

-

The name sounds perfect . It fits neatly next to those of Messrs. Leak, Sugden, Walker , Grant, Lumley, and others of Britain's...

-

Things didn't start off auspiciously. I'd been after Symphonic Line's Klaus Bunge for more than a year to send me the Kraft...

-

Hey, we were in earthquake country, the land from which Carole King may have received inspiration to write, "I Feel the Earth Move...

-

If it's rare to go to an audio show and hear most of a company's products set up properly in multiple rooms, it's rarer sti...

-

The Jadis Eurythmie speakers ($37,000/pair) arrived in a multitude of oversized boxes. Importer Northstar Leading the Way's Frank G...

-

Today, Sony announced an end to production on all MiniDisc players. In a few years, MiniDisc production will cease as well. I know w...

Market information

Blog Archive

-

▼

2012

(194)

-

▼

December

(27)

- Wilson Audio Specialties Alexandria XLF loudspeaker

- Devialet D-Premier D/A integrated amplifier

- Sonic Youth, the Eternal

- 21 More Records from 2012

- The Road to Analog-Sounding Digital: Are We There ...

- First Time Ever: Mahler Download in DSD

- There's a lady who's sure all that glitters is gol...

- The 2011 Richard C. Heyser Memorial Lecture: "Wher...

- U-Turn Audio Orbit on Kickstarter

- Recommended Components #1

- Autographed Pat Metheny The Orchestrion Project Bl...

- GigFi - Find Who's Playing Near You

- Grado HP 1 headphones

- Remix: Hugsnotdrugs Remix of Crystle Castles "Pale...

- Best Jazz Albums of 2012

- TDK’s A73 Life on Record Wireless Boombox

- TDK’s A73 Life on Record Wireless Boombox

- Listening #120

- Whole Lotta Horns for the Holidays

- Yamaha GH1B digital home music system

- My Favorite Records of 2012

- Mark Levinson No.53 Reference monoblock power ampl...

- Followup: The British Invasion Visits NYC at In Li...

- The Entry Level #24

- Dave Brubeck, R.I.P.

- DeVore Fidelity Orangutan O/96 loudspeaker

- KEF LS50 Anniversary Model loudspeaker

-

▼

December

(27)

Wilson Audio Specialties Alexandria XLF loudspeaker

Can a loudspeaker possibly be worth that much? Add $10,000 for speaker cables, and that's what I paid for my first home in 1992. Today, the average American home costs around $272,000, which is likely less than the cost of an audio system built around a pair of Alexandra XLFs.

Think no one spends that kind of money on a music system? Don't kid yourself. Many people can afford it, and many spend it—though not as many as should. We need to educate those people! Anyone want to fly me to Monaco on a goodwill mission?

The real question is this: Is the XLF's sound worth that expense?

I know a pair of speakers can be worth at least $158,000: I've heard the XLF's predecessor, the Alexandria X-2 Series 2, in a few systems over the past few years, including the one in the living room of recording engineer Roy Halee, driven by a pair of big Boulder amplifiers. I sat there for an enjoyable afternoon, mesmerized by, among other things, the X-2s' exceptional transient and microdynamic delicacy, massive macrodynamic scale, bass precision, and top-to-bottom coherence. It's a sound that demands respect: This speaker performs at a level only a few others can manage.

I also know that a pair of speakers can be worth $65,000: At home, I listen contentedly and with great appreciation to a pair of Wilson MAXX 3s. Not an evening of listening goes by that I don't remind myself how lucky I was to be able to buy these speakers, which are part of a system I never imagined I'd be able to own.

Well, actually, I did imagine it years ago, as I lived vicariously through the writings of J. Gordon Holt, Harry Pearson, and others, when the total cost of my audio system was only a few thousand dollars: Denon direct-drive turntable with AC motor, Lustre GST-1 tonearm, Dynavector Ruby cartridge, Marcoff PPA-1 head amp, Hafler DH101 preamplifier and DH200 power-amp kits, and Spica TC-50 speakers. And back then, I felt lucky to own that system.

Description

While the Alexandria XLF superficially resembles its predecessor, the Alexandria X-2 Series 2 ($158,000), the XLF does not replace the X-2, which will continue to be available. The XLF is larger, and at 655 lbs is 50 lbs heavier, than the already massive X-2; it also incorporates numerous changes and refinements.

The volume of the XLF's bass enclosure is 14% greater than the X-2's. The cabinet walls are thicker, and inside, a newly developed bracing geometry better deals with the XLF's greater production of low-frequency energy. The bass drive-units, though, are the same as in the X-2: 13" and 15" woofers made by Focal. The cones are of Focal's proprietary W material: two layers of woven glass tissue separated by and bonded to a core of aeronautical foam, the mass of which can be precisely varied to match the needs of the particular driver design. The W material is ultra-stiff, ultra-lightweight, and said to be extremely low in coloration. It's also 10 times more expensive to make than the high-quality paper Focal uses for its less expensive subwoofer cones, including the ones used in the MAXX 3. (A few years ago, at Focal's facility in St. Etienne, France, I watched W cones being made by developmentally challenged people, who had been taught to operate the machines as part of a government program to create meaningful employment for them.)

The Alexandria XLF features Wilson's unique, room-optimizing, Cross Load Firing (XLF) porting system. With this latest refinement in owner-designer Dave Wilson's attempt to produce speakers that can be optimized to work well in a wide variety of rooms, you can easily switch between front and rear porting by unscrewing a few bolts and swapping the locations of some parts.

The Alexandria series' rigid "wings" that bracket the midrange and tweeter modules, made of cross-braced sections of Wilson's X material (a proprietary phenolic composite), has been substantially strengthened and thickened. Wilson's composite S material was first used in the Sasha W/P, which replaced the WATT/Puppy. Here, in combination with the X material, it replaces the M4 material used in the Alexandria X-2's midrange baffle, and is claimed to audibly and measurably reduce midrange noise and coloration. Wilson's strategy has long been one of relatively large midrange drivers that cover almost the entire midrange without being interrupted by the crossover. However, to avoid high-frequency beaming, this necessitates the two 7" carbon-fiber/paper-cone midrange units handing off to the tweeter at the unusually low frequency of about 1kHz. This is why one of the most significant upgrades in the XLF is its new Convergent Synergy silk-dome tweeter, made for Wilson by Scan-Speak. This replaces the inverted titanium dome used in the X-2 and is built to Wilson's specifications by Focal, variations of which have long been used throughout much of the Wilson line.

While the new tweeter superficially resembles versions used by other manufacturers, Wilson's specific requirements took three years of development to achieve the high power handling, low distortion, and wide bandwidth required by Wilson's crossover strategy—all of which the inverted titanium dome had successfully achieved. The new silk dome meets the goals of low distortion and high power handling while surpassing the titanium dome's overall linearity and HF extension. Another silk dome, a variant of the Convergent Synergy, acts as a supertweeter and fires to the rear from the top of the upper midrange module.

Living like the 99%, listening like the 1%

Had Wilson Audio Specialties been looking for a space in which to demonstrate the efficacy of Dave Wilson's group-delay technology, in particular the Aspherical Group Delay adjustability (see below) implemented in the Alexandria X-2 and the new Alexandria XLF, they couldn't have found one more challenging than my listening room, which measures only 15' by 21' by 8'.

The room itself is not the challenge. In fact, its acoustics have been measured and found to be reasonably linear, and particularly excellent in terms of decay, which one acoustician described as "ideal," thanks to my walls of LPs. Even when not being played, vinyl sounds good. Nor was the challenge one of shoehorning into a ground-floor room two speakers, each one 5' 10" tall, 19" wide, 28" deep, and weighing 655 lbs. Like all of Wilson's large speakers, the XLFs ship in pieces, the massive woofer cabinets rolling out of their crates on casters. The total shipping weight per pair is just under a ton: 1910 lbs. And let's leave aside for the moment the not-insignificant problem of taming the combined output of two enormous woofer boxes placed just a few feet from the room's corners.

The seemingly insoluble dilemma was how to create a coherent soundfield from two tall stacks of drivers sitting just 94" from the listening position. And yet, as unlikely as it seemed, particularly to me, Wilson's Peter McGrath was convinced that the XLFs would, in my room, work as well as if not better than the MAXX 3s. But then, I'd been convinced the MAXX 2s and 3s wouldn't work here, and they did—the 3s better than the 2s, because of the 3s' increased driver adjustability.

Setup

An audiophile friend helped me unbox the Alexandria XLFs' many crates, remarking as we went on Wilson's fanatical attention to detail and the precise fit'n'finish of all parts—even the ones owners are unlikely to ever see once the speaker is assembled.

Article Continues: Page 2 »

| | |||||||||||||

Source : stereophile[dot]com

Devialet D-Premier D/A integrated amplifier

But some products demand a complete revision of a system's architecture. Such was the case with Devialet's D-Premier ($15,995). Not only is this French product an integrated amplifier, with phono and line analog inputs; it has digital inputs and an internal D/A section. And since v.5.5 of its operating system, the D-Premier can also act as a high-resolution WiFi audio streamer, working with Devialet's Asynchronous Intelligent Route (AIR) client for Macs and PCs. At a stroke, the D-Premier replaces streaming program, USB or other computer audio interface, D/A processor, preamplifier, power amplifier, and many cables. And all is contained in a beautifully finished aluminum case about the size of a small pizza box and just over an inch thick.

I first saw and heard the Devialet D-Premier at the 2010 Consumer Electronics Show, but it was not until a year later that Audio Plus Services announced that it would distribute the D-Premier in North America. I received a first review sample in 2011, then a second, to use with the first as a pair of monoblocks, in early summer 2012—but first I needed to clear my decks of more conventional products that I was reviewing. I am now kicking myself for having waited so long.

Technology

Devialet SAS is a French company, founded in 2007 by Pierre-Emmanuel Calmel and Mathias Moronvalle, colleagues at Nortel France's R&D Lab, to develop a new type of amplifier developed by Calmel. Called ADH®, for Analog Digital Hybrid, this patented topology connects a small, high-voltage, but low-power class-A amplifier directly to the speaker, with then a parallel class-D stage providing the necessary current. This is reminiscent of the innovative "current-dumping" circuit developed by Quad in the mid-1970s, though the Quad circuit used a class-AB current amplifier. However, the AHD circuit differs significantly in detail from Quad's, and is considerably more complex. Extraordinarily, there only two resistors and two capacitors in the analog signal path!

I discussed the D-Premier's topology with M. Calmel at the 2011 CES. The analog input signals are converted to digital with an A/D converter, a Texas Instruments PCM4220, running at 96 or 192kHz—the former is the default—before being applied to the volume control, which operates in the digital domain and is implemented in a 32-bit floating-point DSP chip, along with a soft-clipping function and crossover filters when required. All signals are then converted back to analog by two Burr-Brown PCM1792 chips—a high-quality, 24-bit, two-channel, current-output device operating at up to 192kHz. Just half of the DAC is used for each channel, and the current output of the DAC is converted to voltage with a resistor and fed directly to the class-A amplifier—the analog signal path from the DAC output to the loudspeaker terminals is only 2" long. In effect, the DAC swings the high voltage required to drive the speaker output, and the class-A amplifier therefore works at unity gain, as a voltage follower, so that its performance can be maximally linear at high frequencies.

To provide the current to drive the loudspeaker, a four-phase, multilevel digital amplifier—four switching stages, staggered in time—is added in parallel to the class-A amplifier. It is slaved to the class-A amp much as in a car's power steering, where the driver turns the steering wheel to indicate how much he wants the wheels to turn, and a servo-controlled hydraulic system actually turns the wheel.

Conventional class-D amplifiers suffer from high levels of ultrasonic switching noise riding on their outputs, which mandate use of a hefty low-pass filter between the output stage and the speaker terminals. In the D-Premier, there is no LC filter on the class-D amplifier's output; instead, the analog amplifier provides a very wide-bandwidth correction signal that cancels the ultrasonic switching noise that would otherwise be present.

The power supply is a 600W switch-mode type offering 2100W peak and incorporating full power-factor correction. Because of the high switching frequency, the planar transformer can be tiny. There is much more to the D-Premier's innovative and elegant circuit that I don't have room to discuss here; I refer you to a white paper that can be downloaded here. But the entire package offered by the D-Premier appealed to my sense of purity—it is no bigger than it need be to do what is intended.

Setup

I had to slide off the section of the D-Premier's top plate that covers the rear panel in order to be able to use my preferred XLO Reference 3 AC cable, the plug of which would have been too big to reach the recessed IEC mains jack. The D-Premier offers extraordinary flexibility in how its inputs can be arranged—see the diagram of its rear panel. Using the Configurator app, downloadable from the Devialet website, the user sets up the amplifier as he needs and burns the configuration as a text file to an SD card. Inserting this card in the rear-panel slot and turning on the amplifier updates its internal state. I used the factory default configuration, which offers two pairs of analog inputs (one of them phono, to be tested in a Follow-Up review) and five digital inputs: two TosLink, two S/PDIF on RCAs, and one AES/EBU on an XLR jack. There is an HDMI port, currently unused, and the D-Premier is WiFi capable.

The only control on the amplifier itself is a discreet On/Off/Sleep button at the center of the front panel. When the amplifier is on, a gentle amber circle is projected onto the surface beneath the front of D-Premier. All other controls are carried on the remote control. A large rotary knob adjusts the volume. A single button above the volume control duplicates the On/Off/Sleep button; three other buttons control Input Select (consecutive pushes cycle through the inputs, each starting with the volume control set to "–40.0dB"), Bass high-pass filter On/Off (when configured for use with a subwoofer), and Polarity Inversion. These buttons can also be used to control channel balance and tone-control selection, when the amplifier is appropriately configured. The small, circular, color display on the amplifier's top panel indicates the input in use, the volume level in dB, and the sample rate for digital inputs. If no datastream is present, the digital input's name illuminates in red; it turns black if valid digital data are detected. The D-Premier goes to sleep if no music has been played for 20 minutes or so.

To use the D-Premier's WiFi connectivity, Audio Plus had supplied me with an Apple Airport Express programmed to set up a network called "DevialetAudio." When turned on, the D-Premier looks for a network with this name and logs on. To play music over this network, you install the Devialet AIR app on your PC or Mac. This then handles the output of music files selected in iTunes, selecting the correct sample rate and transmitting the data over the network to the D-Premier. This runs automatically, and while it doesn't have to be open during use, as the screenshot shows, when open it displays the name of the file playing, its format, sample rate, and bit depth, and the playback time, as well as cover art and various network diagnostics. AIR is currently limited to 24-bit/96kHz, but a free upgrade to handle 24/192 files is promised.

To use the D-Premier's WiFi connectivity, Audio Plus had supplied me with an Apple Airport Express programmed to set up a network called "DevialetAudio." When turned on, the D-Premier looks for a network with this name and logs on. To play music over this network, you install the Devialet AIR app on your PC or Mac. This then handles the output of music files selected in iTunes, selecting the correct sample rate and transmitting the data over the network to the D-Premier. This runs automatically, and while it doesn't have to be open during use, as the screenshot shows, when open it displays the name of the file playing, its format, sample rate, and bit depth, and the playback time, as well as cover art and various network diagnostics. AIR is currently limited to 24-bit/96kHz, but a free upgrade to handle 24/192 files is promised.

When the D-Premier is connected to the DevialetAudio WiFi network, an iPhone/iPad app duplicates the remote control's functionality and the amplifier display, adding the words "My D-Premier" above the volume setting. Touching the input name brings up an Input Select menu, and again, selecting a different input reduces the volume to "–40.0dB." Touching the volume setting mutes the D-Premier; touching the Mute symbol unmutes the amplifier.

Article Continues: Page 2 »

| | |||||||||||||

Source : stereophile[dot]com

Sonic Youth, the Eternal

Crystal Castles: (III)

Pallbearer: Sorrow and Extinction (Profound Lore)

DIIV: Oshin (Captured Tracks)

How To Dress Well: Total Loss (Acephale)

Purity Ring: Shrines (4AD)

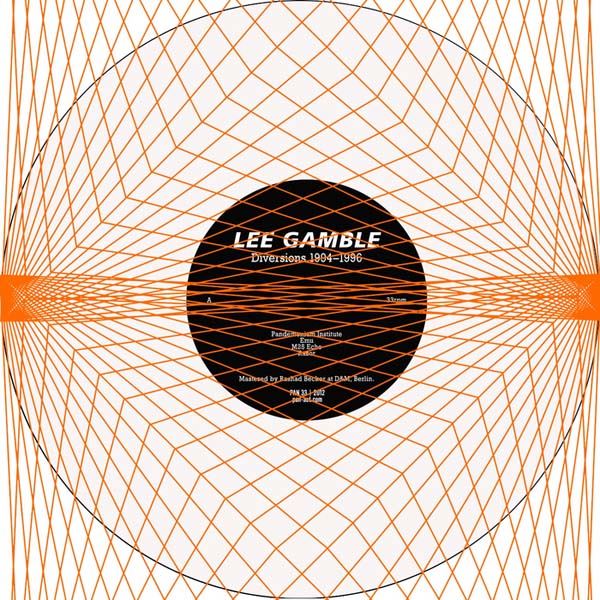

Lee Gamble: Diversions: 1994–1996 (Pan)

Richard Skelton: Verse of Birds (Corbel Stone Press)

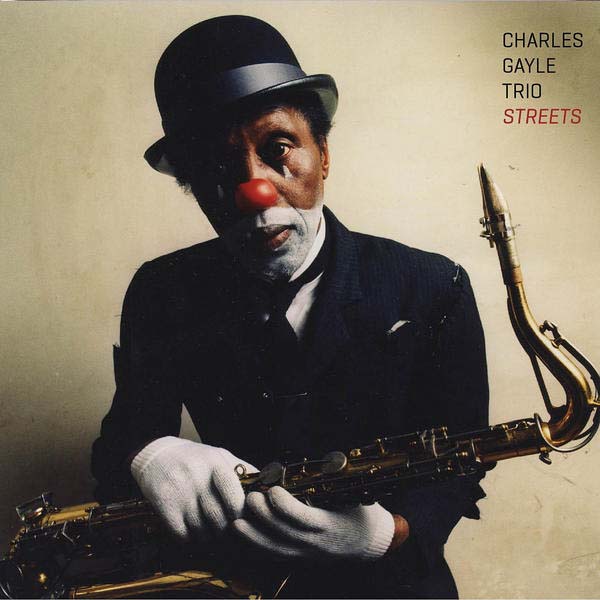

Charles Gayle Trio: Streets (Northern Spy)

Earth: Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light II (Southern Lord)

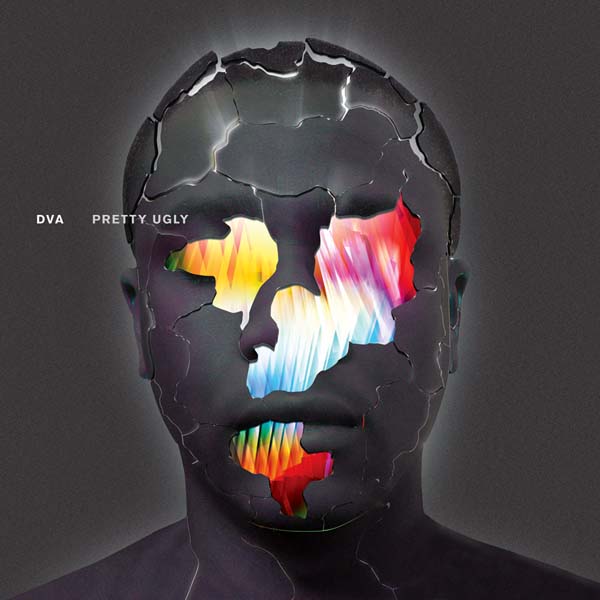

DVA: Pretty Ugly (Hyperdub)

Bob Dylan: The Tempest (Columbia)

Alexander Tucker: Third Mouth (Thrill Jockey)

Leonard Cohen: Old Ideas (Columbia)

Motorpsycho and Stale Storlokken: The Death Defying Unicorn (Rune Grammofon)

Jam City: Classical Curves (Night Slugs)

Mac Demarco: 2 (Captured Tracks)

Chromatics: Kill For Love (Italians Do It Better)

Killer Mike: R.A.P. Music (Williams Street)

Jessie Ware: Devotion (Island)

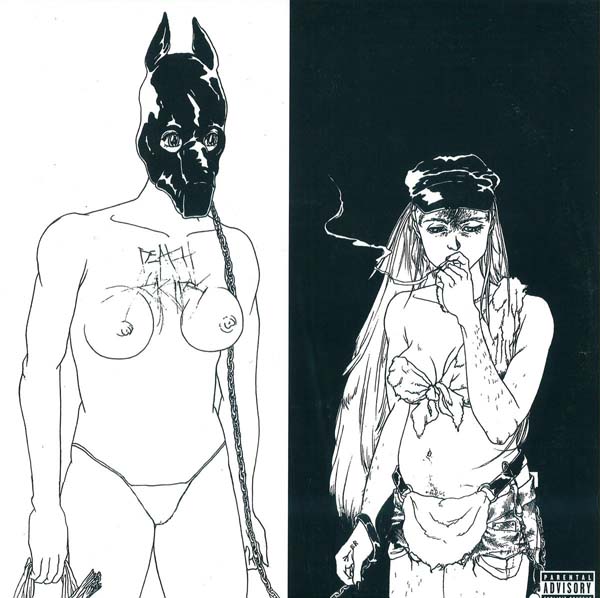

Death Grips: The Money Store (Epic)

Source : stereophile[dot]com

The Road to Analog-Sounding Digital: Are We There Yet?

What does it mean to sound not digital? I remember my early experiences with CDs, and of being nearly uncontrollably excited at their tremendous prospects: 60+ minutes of music, none of vinyl's problems, pure silence in the silent parts, the closest to the real thing we've heard yet. The idea of perfect sound right now—let alone forever—was exhilarating. I got a CD player and some CDs and listened. Instead of music, what came out of my hi-fi sounded shrill, brittle, lifeless, synthetic. What the heck? Had the engineers responsible for this Frankenstein's monster of sonic parts listened to their creation before loosing it on the world?

The Compact Disc was never the undisputed heavyweight champion of perfect sound its promoters claimed it to be. Some people learned to live with CDs without ever learning to love them. Thankfully, CD playback no longer always sucks. Some CDs even sound good. They sound like good-sounding CDs.

The LP, on the other hand—the entire experience of listening to vinyl—is still held up by some as the ultimate meeting of music and mind, body and soul.

File-Based Playback to the Rescue

The next step in our sonic evolution is computer audio—or, more specifically, file-based playback. It seems inevitable that a new sound technology's first steps must be halting ones: 78rpm discs' maximum of three minutes of playing time per side (and the earliest 78s had only one side); CD's brick-wall upper-frequency limit of 22.05kHz; and the scourge of file-based playback, the low-resolution MP3. But those of us who care about the quality of our sound are overpaying for MP3s. Not only have we transcended the sonic pitfalls of lossy compression, we've surpassed CD quality: that brick wall makes no sense in the virtual world, just as paying for lossy downloads can no longer be justified. The remaining paid-MP3 services are mainly run by megacorporations trying to hold on to the last sources of profit that can be squeezed from an impossible business model while being scavenged by pirates.

Which brings us to high-definition (HD) download: Music recorded using a pulse-code modulation (PCM) format, 24 bits and a sampling rate higher than CD's 44.1kHz can sound more natural than a CD. And the higher the sampling rate, the more potentially natural the sound. The other HD factor is Direct Stream Digital (DSD), which stomps all over CD-quality sound, offering proof that CD's brick wall of 16 bits and 44.1kHz was actually made of straw.

I offer up as evidence . . . listening. If you listen to the same recording in hi-def and on CD, you'll hear what I'm talking about. What you'll hear from the hi-def recording is a more elegant and smooth dynamic swing, greater image stability and specificity, richer tone colors (ie, greater harmonic complexity), and attacks and decays that will make your senses stand at attention. All of digital's rough edges have been refined into a natural-sounding patina.

Yield to Natives

To my ears, the best file-based HD music sounds as naturally musical as vinyl. That's not to say that HD digital sounds like analog; it's to say that file-based HD playback can sound as musically involving as vinyl, while not sounding like vinyl. For my way of listening and enjoying, that's great news, and means that everyone should own a turntable and some way to play back file-based HD music. Some recordings sound best on vinyl, and some sound best as file-based HD music. Typically, the closer to a recording's native format you get, the better off you'll be sonically.

So any digitally recorded HD master will be best served by its original format. When it comes to analog recordings, we smack into the wall of preference, but it's clear that CDs can't compete with LPs or HD downloads. Heck, CDs can't even compete with ripped CDs. Analog recordings sound great on vinyl, and the closer you can get to the original vinyl release, the better. Analog recordings can also sound great when delivered as HD files, as long as the process of converting the analog signal to digital is done with care. Some record labels, typically smaller independents, offer free CD-or-better-quality downloads with purchase of one of their LPs, which solves the problem of choice by giving you the best of both worlds.

The other bit of good news is that most people already own a computer, and most computers can be made into music-serving machines that will whomp most CD players' butts. I know this is a terrible thing for some people to hear, but advances like high-definition downloads, memory-based playback, and asynchronous USB really do work. What's more, they serve the music, not some engineer's idea of how best to squeeze sound into a too-small container. It's win-win or lose-lose, depending on how loose you are when you dance.

We're in the passing lane of our music-reproducing journey. High-definition PCM and DSD downloads have finally allowed digital to join vinyl in offering up a truly musically engaging experience.

Source : stereophile[dot]com

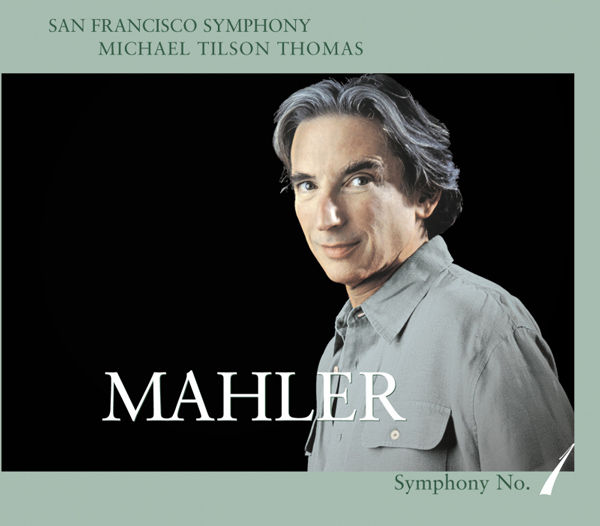

First Time Ever: Mahler Download in DSD

The Mahler 1 files, available in four formats, are all derived directly from San Francisco Symphony's master, not from a copy of the SACD. The formats include two DSD formats: DFF and DSF. For those whose computer playback software or DACs are not equipped to play DSD files, 24/96 and 16/44.1 PCM files in WAV format are also available.

WAV files are larger than the usual FLAC format used for downloads. When, in 2008, Marenco conducted a blind listening test in which she first downloaded 320kbps MP3, FLAC, and WAV files of the same pieces music and then played them back, everyone present felt the WAV sounded cleaner in the low end of the sonic spectrum.

The good news, for DSD lovers, is that DSF files contain metadata and download as fast as 24/96 WAV files. In Marenco's opinion, they also compare sonically with 176.4 and 192kHz PCM. Then again, Marenco is one of the major champions of DSD, which she touts as superior to PCM. Her DSD information site offers both a complete discussion of DSD and why its proponents consider it superior, and a "most commonly asked questions" FAQ.

For those unfamiliar with Mahler's First Symphony, it is possible to audition the recording on the download site. Most alluring are its "Frère Jacques" movement and unmistakable Jewish folk themes, which conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, whose grandparents were the founders and pioneers of the American Yiddish Theater, has in his DNA. And, because it is Mahler, it abounds in those huge emotional swings and tremendous outpourings that make his music an audiophile favorite. You can get a taste of MTT discussing Mahler at the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra's Keeping Score website, and hear the whole program on SFS's 2-disc Keeping Score DVD and Blu-ray devoted to Mahler.

Background

In a phone interview, Marenco discussed how the DSD download project began. "At this year's California Audio Show, in July 2012, we shared a room with Sony. When I encountered San Francisco Symphony's recording engineer, Jack Vad, whom I've known for about 25 years, and told him about what we're doing with DSD, he was very excited. After Jack introduced me to the SFS administrative people, I started explaining what I was doing with our microstores and DSD. When I told them that these microstores are designed for labels other than Blue Coast Records who want to release their music in large size WAV or DSD format, they got very excited about opening up some new avenues of distribution."

Marenco is thrilled that Blue Coast Records got access to the DSD master, and was able to work with Jack and Gus Skinas, who had the original files before the SACD was produced, to verify that it was DSD-native. "It's very difficult to get the original DSD masters," she says. "I've been offered a lot of SACDs from major labels to use for DSD downloads, but when I ask them for the original DSD masters instead, I get a look of horror because, especially with legacy recordings, they can't always verify if the master is DSD-native."

She also has a personal attachment to the San Francisco Symphony recording of Mahler Symphony 1. When it was first released, she was on the NARAS surround-sound recording panel that listened to all the surround recordings of the year before nominating them for Grammy Awards, and it was her favorite surround mix. "It sounded spectacular, and the music I loved," she says.

DSD Insights

A growing number of players and DACs play DSD, including models from Playback Designs, Mytek, Benchmark, dCS, Korg, Chord, and EMM Labs. (Others may be announced at CES 2013, January 8–11 in Las Vegas.) There are also a number of music servers that can play DSD files without converting them to PCM, Auraliti's L-1000 being one. As for computer software, both J River and AudioGate for the PC and Pure Music and Audirvana for the Mac can play DSD without converting it to PCM.

Many audiophiles who own SACD players assume that when a hybrid SACD is DSD-native, their player outputs DSD. Alas, this is not the case. According to another major proponent of DSD, Playback Design's Andreas Koch, "The sad story about SACD drives and players is that some of them read the DSD program and convert DSD to PCM before converting to analog. All Philips drives do that. The only drive that I know that doesn't do that is the one from TEAC (the one I use)."

There is also an issue with SACDs that pose as DSD-native when, in fact, the masters were recorded in PCM. Marenco not only refuses to label her music downloads as DSD unless they were originally recorded in DSD or on analog tape, but also asks to speak to the engineer who recorded the music, or those that attended the session, to verify its provenance.

She is currently developing a white paper for labels, distributors, audio engineers and schools that will explain what DSD is and set standards for receiving properly prepped DSD files for download. Among those standards is the importance of historical information about sessions.

Marenco is especially enthusiastic about the quality of the DSD masters that her site offers. "The difference between the DSD two-channel layer on an SACD and what we sell is that we sell the DSD mix prior to authoring for SACD. The SACDs we receive back from the plant never sound as good as the DSD masters that we've mixed. There's so much variation in the discs that come back to me that I suspect there are errors introduced on the disc itself. Our ability to offer a DSD file before it has been put on a disc makes a profound difference."

Source : stereophile[dot]com

There's a lady who's sure all that glitters is gold...

Before I sat down to write about the new Led Zep concert film, Celebration Day, I watched the old Led Zep concert film, The Song Remains the Same”. Back in that now much–maligned decade known derisively as the 70’s, the creators of Zoso, who were then ascending the stairway to mega–rock stardom, made a movie. Not a concert film exactly but a concert film interspersed with so–called “fantasy” bits, all of which—excepting the utterly ridiculous mafia scene, complete with werewolf, at the film’s opening-—unfold while the band plays tunes from a three night stand at Madison Square Garden in 1973. While Page climbs mountains seeking knowledge in his fantasy sequence and Bonzo races dragsters and plays snooker, Plant’s fantasy, where he’s a knight without the shining armor (probably not in the budget), comes complete with swordplay and damsels in distress, all while “Rain Song” and the film’s title tune play at full volume. Time it seems has even softened opinions of this amusingly amateurish oddity. Now regarded more as a charming curio than the self–indulgent, half–baked nonsense which most critics and many fans pronounced it to be at the time of its release, it’s no accident that This Is Spinal Tap took many of its now famous comedic cues straight from The Song Remains the Same. The opening of “Since I’ve Been Loving You” is clearly echoed in the scene of Nigel playing his solos. Or the flavor of Peter Grant’s tirade in the dressing room shows up in the characters of both Ian and Nigel.

Yet the old band reunites phenomena is changing the rules of record listening and in the case of Celebration Day, a concert film boxed with a two CD live record, I held my breath as the opening notes of “Good Times Bad Times” rang out. By the third tune, the ever–unfading “Black Dog,” I was completely in love. Is it that I was so glad to see and hear Led Zeppelin back together, with Jason Bonham who from the forehead down looks more like his father every year, that I am willing to suspend my critical judgment? Are we so damned starved by all these years of No Zep, that some Zep, any Zep, is better than no Zep at all?

I’d like to think my ears, not to mention my brain, still work and the decently though not wonderfully recorded Celebration Day, is genuinely great, both film and records. In my opinion this is first class, top shelf, make–you–want–to–cry Led Zeppelin. The proof lies in the fact that you never even notice the subtle changes that make it possible for this band of almost 70somethings to sing and play this well. Everything is slighter slower and pitched down a step or two to allow Plant to sing it. The screeching high notes of yesteryear are gone. Having a young drummer also helps, as Jason Bonham drives the proceedings with more than an echo of his father’s legendary thump. Even with Jason’s best efforts, it’s still easy to see why Bonzo’s death left the band with such a void they were unable to carry on. He was always Zep’s not–so–secret weapon.

The varied set is a triumph throughout in tunes like “Rock and Roll,” “Kashmir” and a surprisingly sharp, “Nobody’s Fault But Mine,” where just for a moment the years melt away and the nasty boys of 1973 return with all their youthful ambition and power intact. They are on top and in charge from the first notes. And in the film everyone seems to be having a good time to boot. At various high points during the show, a tribute concert for Ahmet Ertegun, Page and Plant exchange sly smiles that say, `Yeah we still got it!” And aging or not, they still do.

Source : stereophile[dot]com

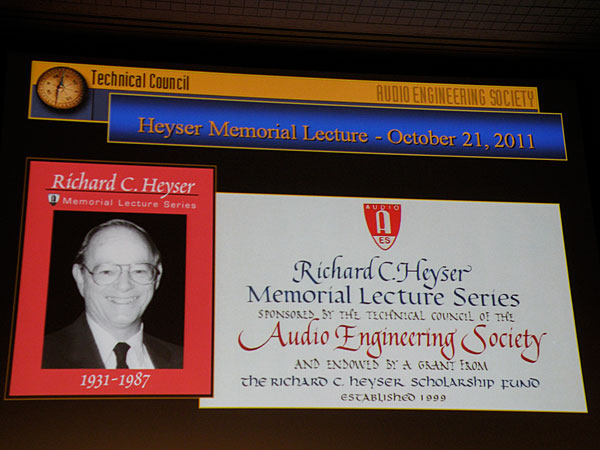

The 2011 Richard C. Heyser Memorial Lecture: "Where Did the Negative Frequencies Go?"

The AES website notes that the Richard C. Heyser Memorial Lecture series was established in May 1999 by the AES Technical Council, the Board of Governors, and the Richard Heyser Scholarship Fund to honor the extensive contribution to the Society by this outstanding man, widely known for his ability to communicate new and complex technical ideas with great clarity and patience. The Heyser Series is an endowment for lectures that will bring to AES conventions eminent individuals in audio engineering and related fields.

With thanks to the AES Technical Council for their permission, the preprint of John Atkinson's lecture is presented here.—Ed.

Richard C. Heyser Memorial Lecture: "Where Did the Negative Frequencies Go?"—John Atkinson, Editor, Stereophile magazine

"Even a cursory read of the academic literature suggests that in audio, all that matters has been investigated and ranked accordingly. But his 40-year career in music performing, record engineering and production, audio reviewing, and editing audio magazines leads John Atkinson to believe that some things might be taken too much for granted. The title of his lecture is a metaphor: all real numbers have two roots, yet we routinely discard the negative root on the grounds that it has no significance in reality. Perhaps some of things we discard as audio engineers bear further examination when it comes to the perception of music. This lecture will offer no real answers, but will perhaps allow some interesting questions to develop."

Essential reading for the informed audiophile: the AES anthology of the late Richard Heyser's writings

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. It is an honor to have been invited to present this evening's lecture in memory of the late Richard Heyser. Audio theorist, engineer, reviewer, scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, inventor of Time Delay Spectrometry, and Audio Engineering Society Silver Medal recipient, Dick was a man I was privileged to have met just the once, at an AES meeting in London in March 1986. His comments that night gave me much to ponder in the years ahead. I was also in the audience for the presentation of his final two papers to the AES, given by telephone at the fall 1986 AES Convention in Los Angeles, from his hospital bed. I had not realized until that evening that his illness was terminal.

My wife got to know Dick well when they both worked for Audio magazine; she remembers going round a Consumer Electronics Show with him. Before entering each exhibitor's suite, Dick would cover up his name badge: "That way they won't know who I am," he said with his usual modesty, "and I will hear the system as it really is, not how they want 'Richard Heyser' to hear it."

It is also an honor to follow in the footsteps of such visionaries as Ray Dolby, recording engineer Phil Ramone, futurist Ray Kurzweil, mathematicians Manfred Schroeder and Stanley Lipshitz, film-sound pioneer and editor Walter Murch, Andy Moorer of Sonic Solutions and Adobe, Roger Lagadec, Kees Schouhamer Imminck (who developed the optical data-reading technology used in the CD), Karlheinz Brandenburg of MP3 fame, and acoustician Leo Beranek.

When Robert Schulein of the AES Technical Council e-mailed me last summer to invite me to give this lecture, I was sure that a mistake had been made. The gentlemen above invented the future. By contrast, I am just a storyteller; worse, I am a teller of other people's tales, including tales told by some of the people above.

"Writing about music is like dancing about architecture," Laurie Anderson was once supposed to have said, and to be an audio journalist is not too different. However, as a generalist in a world of intense specialization, I think I can dance a step sufficiently varied to cast some interesting shadows.

I am sure that some of the questions I will ask in the next 50 minutes or so have already been answered, perhaps even by one or more of the people in this room. Nothing I will say is either original or new. Much of it has been examined in articles I have written and speeches I have given over the past decades. However, it is unlikely that everything will have ever been grouped together in the same presentation before. And, of course, given the large amount of ground I will be covering, I am well aware that I am skating over crevasses of deeper understanding. So I beg forgiveness for the inevitable generalizations.

Early Days

I had a schizophrenic education. On the one hand, I was an academic overachiever in the sciences. On the other, music meant more to me than any other interest at school, and I continued playing bass guitar in bands, first while I kept my nose to the scientific grindstone at university, and later when I took a job in scientific research.

I started out working, in a government laboratory, on the development of LEDs. This is my ID card at the lab—long hair was mandatory for government workers at the end of the 1960s, of course.

One of my tasks was to grow my own junctions, using a slice of a zone-purified n-doped gallium phosphide crystal and depositing a layer of p-doped material on it with a vapor-epitaxy oven. I would then cleave the material into individual dies and make transistors from them under a stereo microscope. I would characterize the charge-carrier mobility by measuring the Hall Effect with an enormous magnet—I once stuck my hand in the magnet but felt nothing, despite all the ions in my nerves presumably pressing against one side. I later worked for a mineral-processing laboratory, where I learned to pan for gold, among other skills.

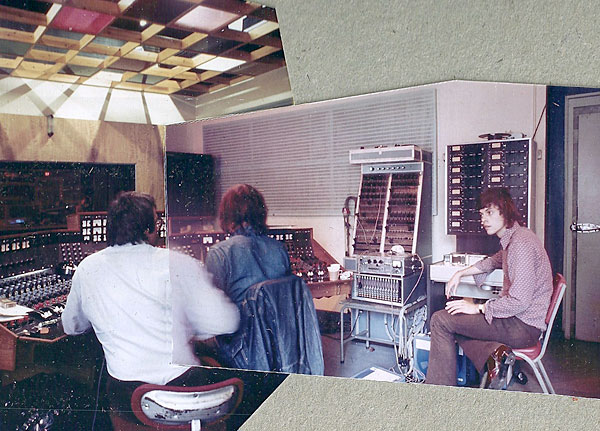

But even as I began slowly climbing the scientific ladder, music pulled even more strongly, and I resigned from the lab in July 1972 to join a band that had just been signed to Warner Bros., and was to make an album at Abbey Road Studio and then embark on a tour of America. Well, we made the album, but our manager did a runner with the advance from Warners and the LP was never released. One memory I have of Abbey Road was this young tape op who, one lunchtime when the producer and engineer were at lunch, sat at the console and did a superb mix of one of our songs.

This slide is a montage of two photos I took in Abbey Road's Studio 3—you can see that the tape op sitting by the 16-track Studer machine was a youthful Alan Parsons!

For the next four years I played with other bands, toured, and made other albums, but it eventually became clear that I would need a steadier source of income, and in September 1976 I joined the British magazine Hi-Fi News & Record Review as an editorial assistant. At a magazine devoted to audio equipment and recordings, I felt as if the scientific and musical sides of my brain could finally coalesce. And working on audio magazines is what I have done ever since.

As I said, I am a generalist in a world of specialists. The problem with being a generalist is the vast amount of information published in every field. It is impossible to stay current. Back when the Scientific Method was a radical new idea, and science was the preserve of wealthy gentleman amateurs, it was just about possible for a single person to know everything. But those days are long gone . . . one group of researchers reckon that 1.3 million articles were published in scientific journals in 2006 alone.

I am also old enough that my education in electronics and audio was exclusively based on tubes. Even the logic circuits I constructed at school used tubes! But looking back, I think there was one experience that foreshadowed my career as an audio reviewer. For one of my bachelor's final exams, I was handed a black box with two terminals and had to spend an afternoon determining what it was. (If I recall correctly, it was a Zener diode in series with a resistor.) That experience is echoed every day in my endeavors to characterize the performance of the audio components reviewed in Stereophile—every product, be it speaker, amplifier, CD player, is fundamentally a black box with input and output terminals. All I have to do is ask the question "What does it do?" And remember that testing a product is not just a case of pressing "F9" on the Audio Precision; you are faced with trying to get into the head of the designer and asking, Why did he do it this way? What is the trade-off the designer has felt worthwhile? (There are always trade-offs.) And why?

Concours d'elegance

I am addicted to elegant ideas. When I first realized that the square root of negative 1, i, could be visualized as meaning a rotation of 90° into a second dimension of what was hitherto a one-dimensional number line, it was a moment of satori. In the one-dimensional world of numbers, the concept of the square root of negative 1 is meaningless. But by adding a new dimension, you enter a new, rich reality where i does have meaning.

But it didn't take me long to realize that elegance is not always equivalent to truth. As a teenager, I thought that the hypothesis of the Static Universe propounded by Fred Hoyle, along with Thomas Gold and Hermann Bondi (whose passing significance I'll mention later), was supremely elegant. (And it didn't hurt that, as a science-fiction fanatic, I was familiar with Hoyle's fiction.) Hoyle's idea was that, as the universe expands, it causes new matter to be created, if I remember correctly, at the rate of one hydrogen atom per cubic meter per 1000 years, so that if you took a series of snapshots of the universe, one every billion years, they would all be identical. Of course, as soon as the cosmic microwave background was discovered, Hoyle was proved completely wrong. (This is ironic, as Hoyle had invented the term "Big Bang Theory" to disparage what turned out to be the correct theory.) But the Big Bang Theory means that the universe had a beginning and will have an end, which strikes me as inelegant in the extreme.

A glass of what by rights should be a gas at room temperature

I am also fascinated by things that don't seem to fit. For example, when I first studied the Periodic Table of the Elements, it struck me as very strange that water is a liquid at normal temperature and pressure. If all you knew were the properties of its constituents—two of the lightest elements in the Periodic Table—you would expect water to be a gas like hydrogen sulfide, but less dense and less smelly.

But water obstinately isn't a gas, and we all take for granted that it isn't. In fact, our lives depend on it not being a gas. It takes a deeper knowledge of the properties of water to understand why it doesn't fit.

It is the combination of elegance and apparent anomalies that I will be talking about in this lecture. Which brings me to an explanation of its title:

Article Continues: “What Happened to the Negative Frequencies?” & Science, a Digression »

| | |||||||||

Source : stereophile[dot]com